Books From Banned Countries: Libya

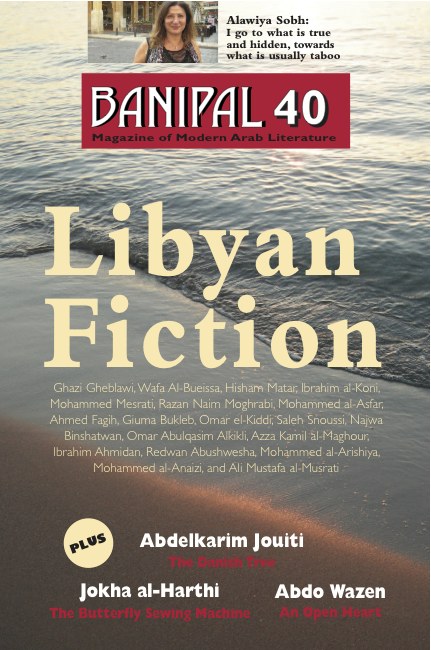

After a brief hiatus, the “In Translation” series returns with one of the lesser known Middle Eastern regions. This week’s installment focuses on Libyan literature.

Once you’re done with their selection, you can ponder that ostensibly silly question “what defines a national literature”? After all, several of the authors presented in the Banipal’s pick don’t live, work and publish in Libya; some don’t even write in Arabic.

What to make of it?

It so happens that literary creativity in Libya is intrinsically linked to the political developments in the country and, unfortunately, this was not always a good thing. The work of a strong generation of authors that formed in the 1960s practically came to a halt “as a result of the arrests of young authors and intellectuals that had been taking place since the mid-1970s”, as Omar Alkikli says in his introductory essay in the Banipal. Alkikli, who spent a decade in prison and was only released in 1988, also points out that the Gaddafi regime didn’t need to lock up a huge number of writers to silence others. He notes that many writers stopped writing in that period and that no new short story writers emerged in the 1980s.

Plenty of authors moved abroad, some more voluntarily than others.

Of those who stayed and continued working, the most interesting ones are probably Ahmed Fagih and Kamel Maghur (even if their involvements with the Gaddafi regime makes this author cringe). Fagih is probably best known for his trilogy Gardens of the Night, which is long out of print in English, so you might go with Homeless Rats or Maps of the Soul. The only translations of Kamel Mughar that I know of are from the Words Without Borders’ Literature from the Axis of Evil, which is a pure delight.

Of those authors who have spent at least part of their working life outside of Libya, the most important and recommended is the intoxicating Ibrahim al-Koni. Probably one of the best known Libyan authors, Al-Koni “extricated the Libyan novel from its inward-looking localism and pushed it outward to form a new offshoot of the Arabic novel,” Taken from his interview in Banipal. Try it for yourself: Curl up with The Puppet or Gold Dust and prepare to be seduced. And if you find yourself fascinated with the otherness of Al-Koni’s desert, heed the advice he gave to the novel’s translator Elliott Colla: “see his desert as Melville’s sea…”

Some younger authors started working in the 1990’s after the laws were somewhat loosened. Among the most important ones are probably Maryam Salama, whose short story From Door to Door, was included in the book Translating Libya.

If you want to know how to exist in a repressive dictatorship, read Mansour Bushnaf’s Chewing Gum.

As far as I know, the short excerpt in Banipal is the only translation of Wafa el-Bourassa’s Hunger Has Other Faces – a book deemed provocative enough to the Gaddafi regime that the author had to seek asylum in the Netherlands, where she still lives today.

We’re back to the “what defines a national literature” question. Yes, you can live abroad and write in a language not native to the country you are from and still be a part of its culture.

Case in point: Hisham Matar and his haunting novels In the Country of Men, The Anatomy of Disappearance, and The Return. Matar was born in New York, lives in London and writes in English. But if you only pick one Libyan author from this list, pick him. If you can’t get to his novels, read his essays that float on the interwebs.

And then there’s Alessandro Spina‘s The Confines of the Shadow: In Lands Overseas. It is, quite simply, one the most fascinating books about the Mediterranean I know of.

Manga fans will know about Asia Alfasi, a Libyan-born Birmingham-based Manga champ. If you don’t know her yet, tarry no longer.

And for the poets among you: Khaled Mattawa, a Libyan-American poet who currently serves as the Chancellor of the Academy of American Poets. He is a prominent translator of Arab poetry and a genius. You don’t have to believe me because the MacArthur Foundation says so. His poem, Now That We Have Tasted Hope, is probably the best-known poem from the time of the Libyan uprising in 2011.