by Charles Irwell

During the trial of Michael Jackson’s doctor, I happened to be at my mother’s house. We watched a news report that detailed the extent of Jackson’s pharmaceutical drug addiction. My mother, a proud NHS nurse of 40 years, shook her head in incredulity at the drugs Jackson’s physician gave him and said “Propofol? God almighty, I’ve only ever seen people get that when they’re dying.”

That was in 2012. Ever since, we have both marveled and despaired at the way in which opiates have run roughshod through middle America. Although much news coverage portrays this problem as one which blights former working-class communities, the truth is that this is a problem which has weaved its way through every pillar of American society like knotweed.

The hysterical anti-drug propaganda of the early years of prohibition, and a lot of the more recent newspeak, portrayed drugs as a problem of migrant communities. A problem without, inflicted upon the rest of law-abiding, white America. Even a cursory look at the statistics of the drug trade reduces such a view to ashes. So pernicious is the problem that, between July 2016 and September 2017, overdoses almost doubled in the Midwest and 80% of sampled heroin users started on prescription opioids. Also, the amount spent on illegal drugs worldwide means that there has always been, and always will be, a commanding share of the market which is made up by functional users who can support their habits comfortably without resorting to theft, penury, and all the rest of it.

Yet, I do not think that drug prohibition was an idea borne from bad faith. Addiction is not fun, in any guise, and ought to be more widely recognized for the disease it in fact is. The way in which drug prohibition, in the words of David Simon, “devolved into a war on the underclass”, is yet another example of how all capital corrupts, and the road to hell is, indeed, paved with good intentions.

The problem was one which every section of society shared. After the Opium Wars and the horrendous business of the India-China trade exploded, not only did the blue bloods of the world get rich on the back of suffering nations, but the poorest, barrel-scraping persons of the world had cheap opium as a medication and an escape.

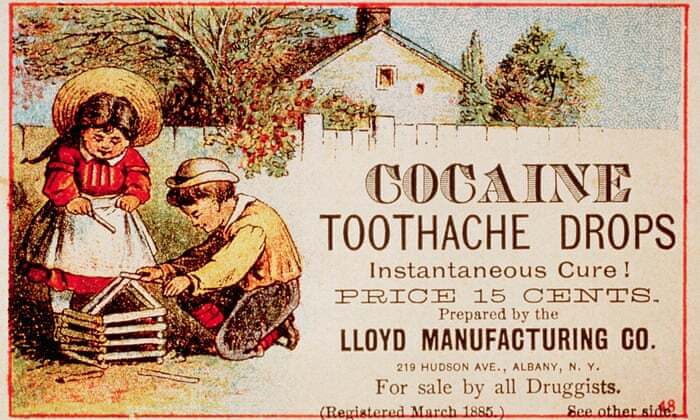

The rhetoric of those who campaigned for drug controls in the early years were on the lines of enforcing medical ethics and standardized practices. In the early twentieth century, as hardcore libertarians unerringly point out, heroin, cocaine and marijuana were all perfectly legal and sold as remedies (heroin is a brand name, not a scientific one). The issue was, in the free-for-all of Western Expansion, quackery was rampant and heal-all, cure-all oils and remedies were, more often than not, filled with dope. Although one could summon a macabre chuckle if one of the world’s Karens started spiking her Herbalife with china white, the effect of such free-and-easy prescription led to widespread addiction, and not only for adults. The drug was used for everything, from mental illness to teething babies.

Medicinal practitioners were not blind to the harm the drug did, and it was from here that the great pushback came from. One of the most vocal opponents of Opium sales, and most well-connected politically, was Dr. Hamilton Wright. In an interview with the New York Times in 1911 titled Uncle Sam is the Worst Drug Fiend in the World, he was quoted as saying:

“Opium, the most pernicious drug known to humanity, is surrounded, in this country, with far fewer safeguards than any other nation in Europe fences it with. China now guards it with much greater care than we do; Japan preserves her people from it far more intelligently than we do ours, who can buy it, in almost any form, in every tenth one of our drug stores. Our physicians use it recklessly in remedies and thus become responsible for making numberless ‘dope fiends,’ and in uncounted nostrums offered everywhere for sale it figures, in habit-forming quantities without restriction. Even in Russia medical practitioners, recognizing the great Sydenham’s declaration that without opium their profession would go limping, have guarded it as one might guard a pearl, for use and against abuse.”

One feels the note of sadness, rage and righteousness within this quote. The parallels between that time and ours – of unregulated drugs, misinformation and cynical profiteering from abject misery – are palpable.

However, the rhetoric of the pushback has a lot to do with what it turned into. The word fiend, when describing those whose lives revolve around taking illicit substances is a good place to start. It sees them as knowing and willing enemies of established order and good taste, rather than often life-long addicts to a drug they had little understanding of and which was often forced upon them by unscrupulous doctors. For example, the amount of wounded civil war veterans that depended on the drug numbered in the millions and, according to David T. Courtwright:

“Even if a disabled soldier survived the war without becoming addicted, there was a good chance he would later meet up with a hypodermic-wielding physician.”

Furthermore, the irritating comparison between the supposed common sense of other nations has the air of one who thinks that this is an issue inexorably tied up with personal responsibility, rather than seeing it as a systemic problem.

Although the eventual ban, heralded by the 1935 International Opium Convention, stopped the sale of opium commercially, it did not stop the production of analgesics which, more often than not, have opium as a key ingredient. In the postwar period, unlike Britain, Canada and a number of others, America did not opt for a national healthcare system, christening it Socialized Medicine in the hysteria and hubris of the Cold War. Such a system would mean that all one would need to do is doctor hop in order to get their fix. Furthermore, with CIA backing, sales from the drug filled the coffers of Chiang Kai Shek, Laotian Hmong rebels, and the Afghan Mujahideen.

Fast forward to the 90s, and further deregulation in the medical sector meant that medication normally reserved for palliative care and theatre work would now become more readily available. Not only this, but with non-reassurance from the pharmaceutical companies that these were not addictive. From depleted working communities, still shrugging off lives of back-breaking labour, to the slow and comfortable white-fences of suburbia, such drugs as Fentanyl, Hydrocodone, Oxycodone, and Morphine would soon re-enter. When these drugs stopped, patients became addicts and started turning to the corners.

From crisis, to crisis. As long as the US Healthcare system remains for-profit, and not enough is done to attack the systemic forces keeping the addiction golem in place, the problem is destined to get worse.

The post The Deep Historical Roots of America’s Opioid Crisis appeared first on Broke-Ass Stuart's Website.