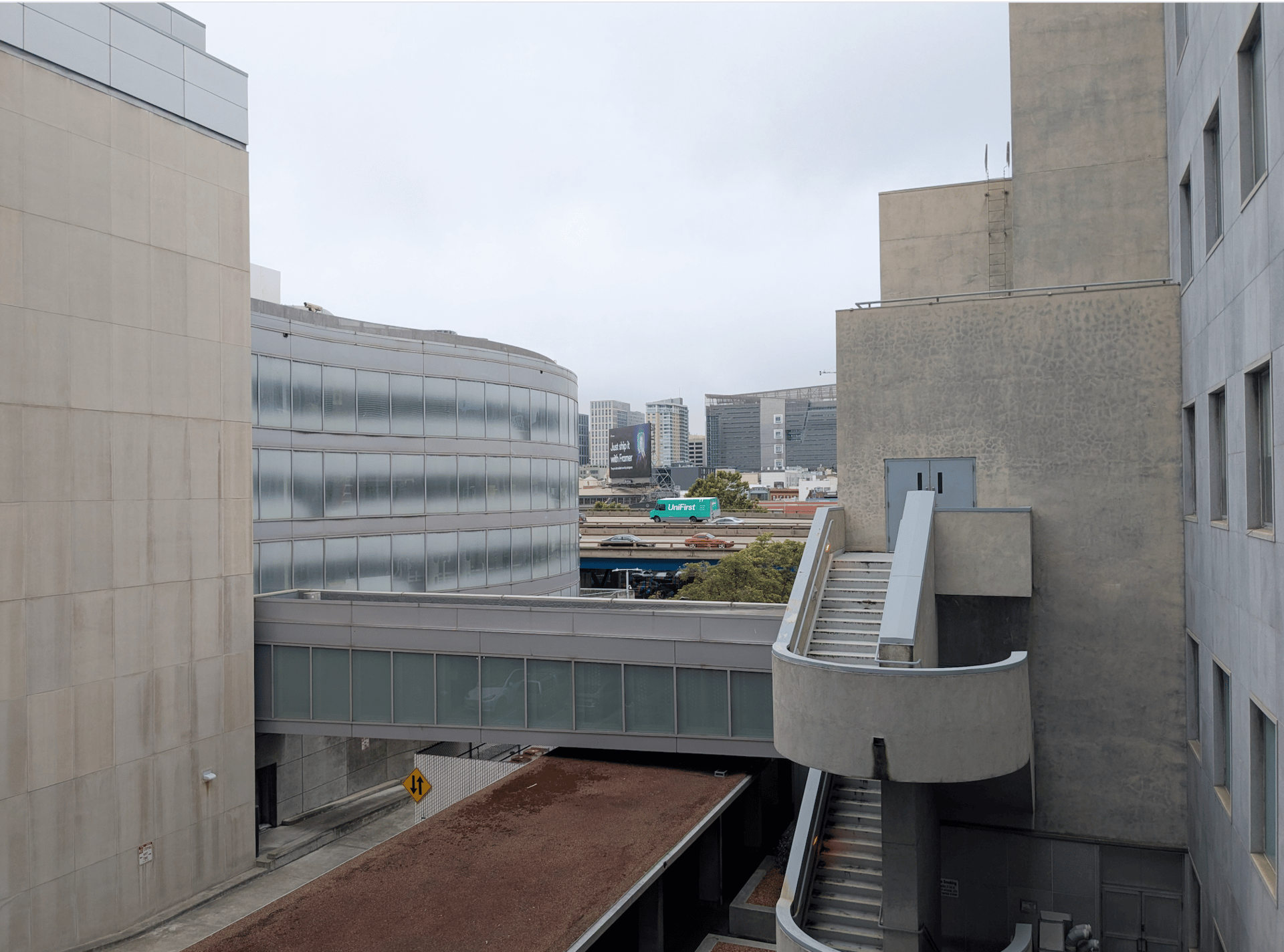

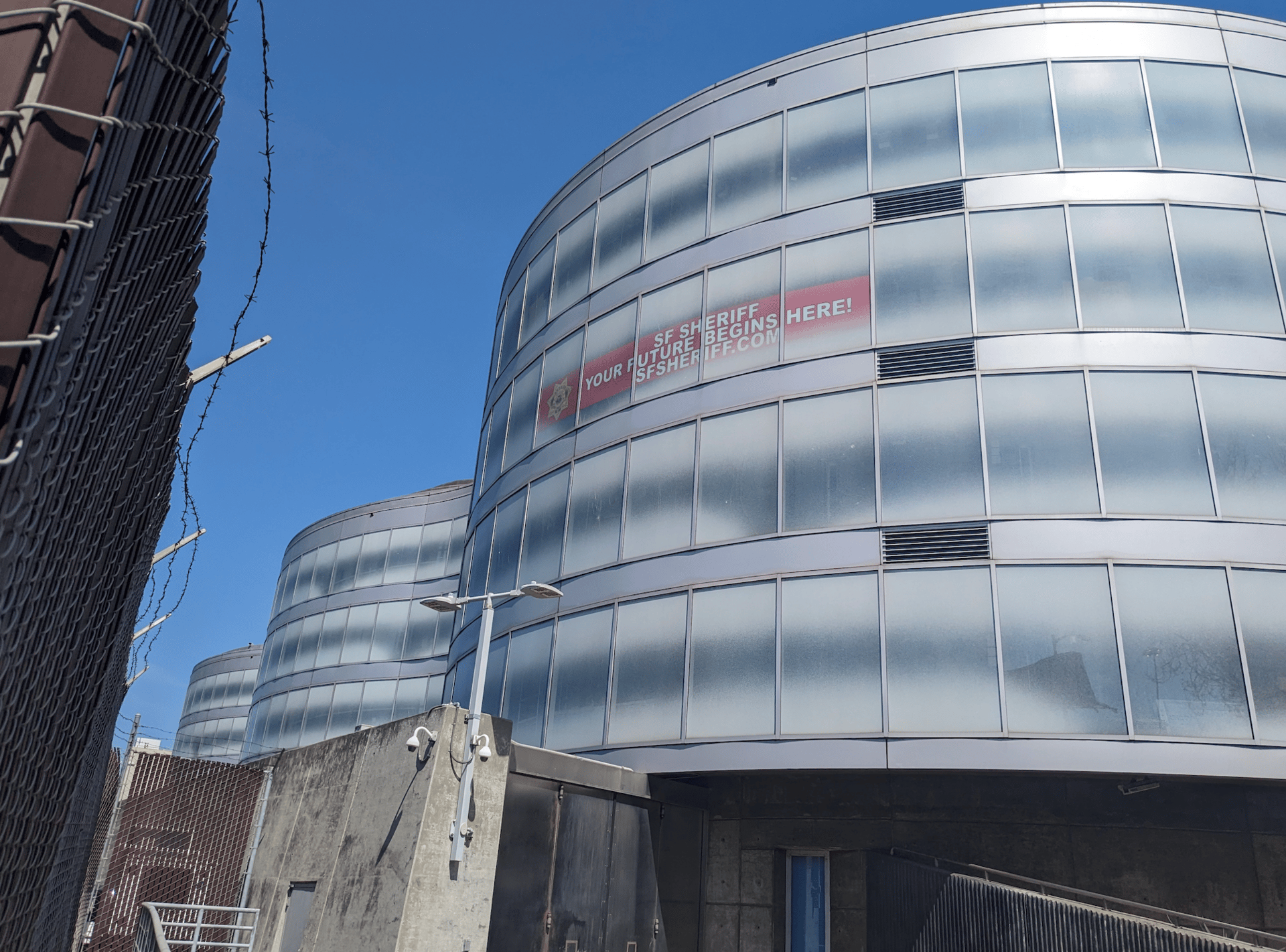

The San Francisco Hall of Justice Complex. Public Domain photo.

by Amy Martyn

This is part one in a series.

The victims were both still alive when people found them in the street, tied up and gagged with socks. Stephen Reid had been shot and later died at San Francisco General Hospital at the age of 26. The other victim, a young woman, survived. The San Francisco Police Department arrested five people a few days later. It was like “something you see in the movies,” a police spokesperson said at the time.

But there is no tidy ending like there would be in a Hollywood movie. The two lead suspects have languished in jail in the thirteen years since, without trial to determine whether they are guilty. Vincent Bell was 31 when he was arrested on accusations that he was the ringleader in the “bound and gagged” case from December 2012. He is now 44 and remains in pretrial detention. His co-defendant Montrail Brackens, 34, said he doesn’t understand why the case is still open. Both have invoked their right to a speedy trial, a process under California law that is supposed to bring a trial in sixty days.

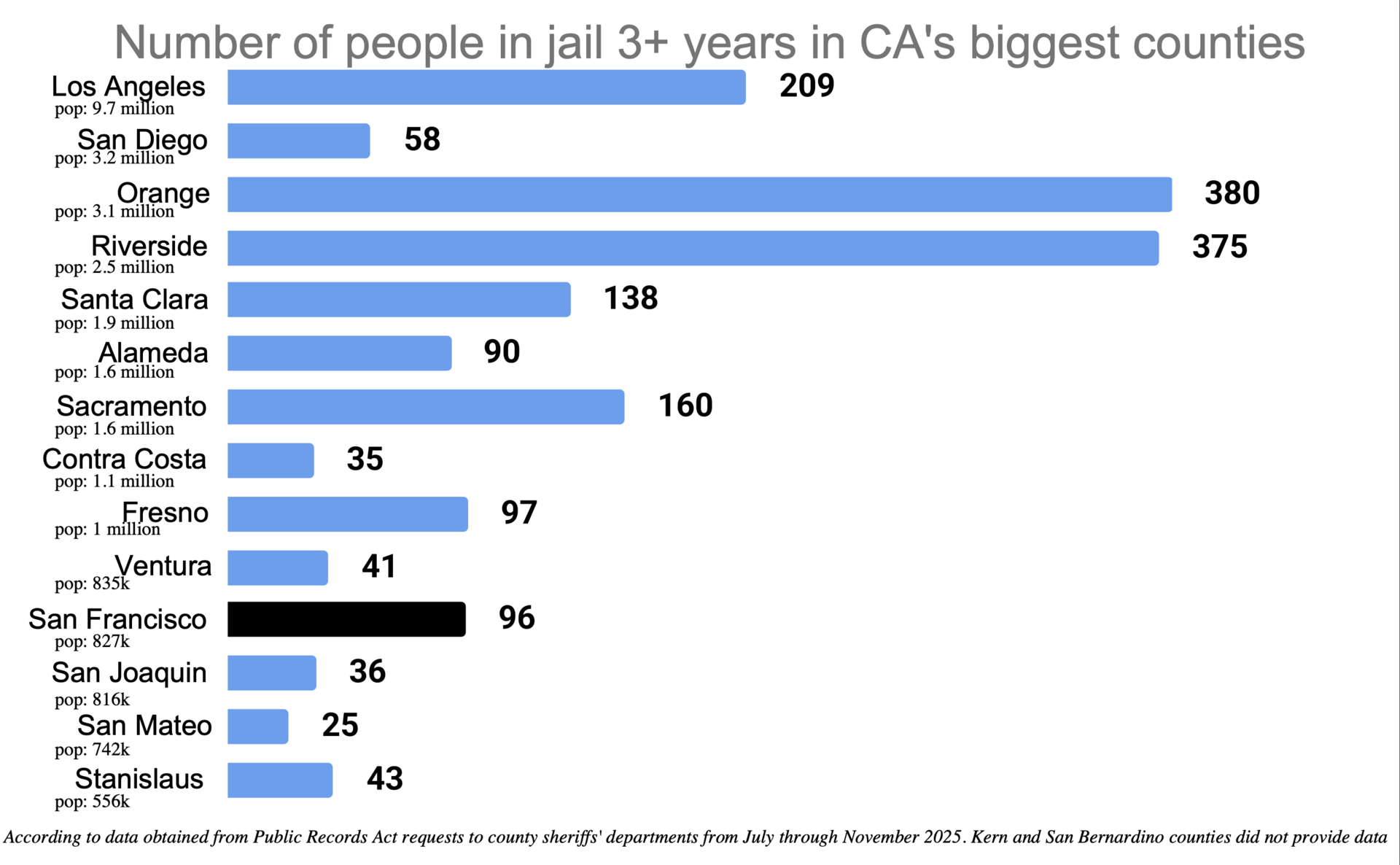

If you’ve ever seen social media posts about crime in San Francisco, you’ve probably seen the comments underneath predicting that the accused would get out of jail the next day. The reality is that San Francisco jails are holding 96 people who have been there for at least three years without trial, according to figures provided by the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department through a public records request.

“This county jail is one of the only places I've ever really seen that you can just sit here for like 10 years and still fight a case,” Brackens told me in an interview at the San Francisco jail system where he has spent more than a third of his life. “I would have preferred a resolution…Why is it so hard to talk about resolving cases? I don’t understand that.”

Bell said he is determined to prove that he is innocent, even though that means spending most of the day in isolation. The jail houses him in administrative segregation because his case is classified as “high-profile.” He compared his situation to the film Groundhog Day. "I try to make every day the exact same in order for the day to go by," he said.

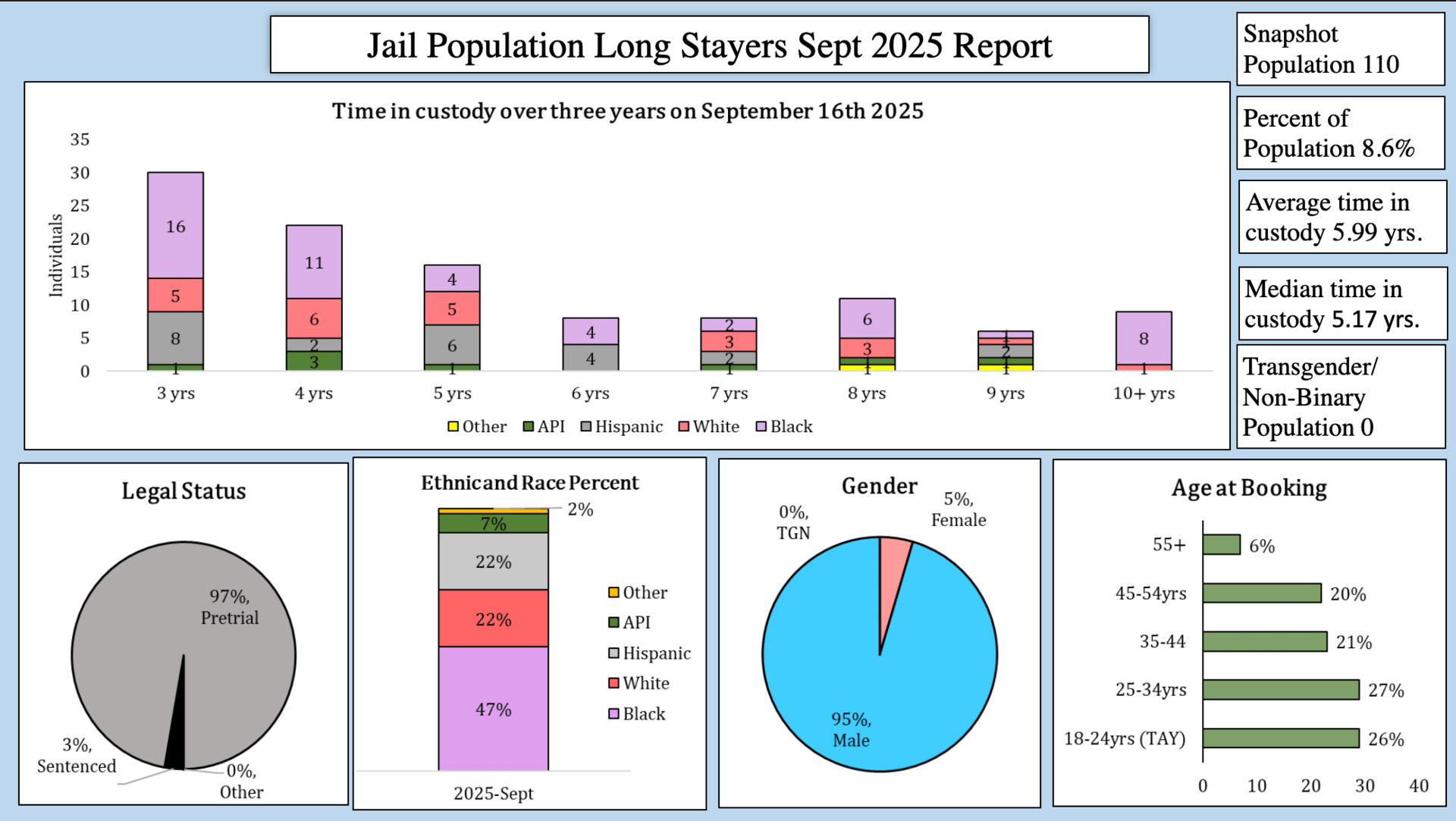

People in jail at least three years are labeled “long stayers” by the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department. They make up 8.6 percent of the jail population, according to a monthly jail population report. A total of 280 people have been in pretrial detention in San Francisco for at least one year.

Some of San Francisco's political leaders and wealthy donors prefer to publicize cases where allegedly violent criminals are released from jail too early. District Attorney Brooke Jenkins has made law and order the centerpiece of her agenda. The average daily jail population is approaching 1,300, the highest it has been since 2020. In a county where Black people make up just 5 percent of the population, the jail population is 42 percent Black.

Hundreds of people have been waiting for years in county jails across the whole state of California. It's a problem that was last highlighted in the aftermath of the Covid-19 outbreak and has only gotten worse. Compared to some other counties, San Francisco appears to have a disproportionately high number of people waiting for years in jail. Alameda County jails, for example, have approximately 90 people waiting at least three years, and Alameda County is twice the population size of San Francisco.

Unlike prison, people in jail have typically not had a trial yet or been convicted. The Sixth Amendment in the United States constitution guarantees the right to a “speedy and public trial.” And California law specifies that people charged with felonies have a right to a trial within sixty days.

Most people facing serious charges won’t get a trial that quickly in San Francisco. They often give up or “waive” that right for reasons beyond their control, such as; overworked attorneys needing more time to prepare or hearings getting scheduled weeks apart because the judge's calendar is full. And if the defendants decide to assert their speedy trial rights later on, they might find that judges will still agree to delays.

Between 2024 and 2025, the median time it took felony cases to reach a conclusion such as sentencing, dismissal or acquittal in San Francisco was 391 days, according to data on the DA’s website. In 2014 the median time was 140 days, less than half of what it is today.

“It’s the most dysfunctional court I’ve ever been in. It’s institutional,” said one defense attorney who spoke anonymously because they compared working in San Francisco to working in a small town.“I feel sorry for people who have never worked in another county. They think [the court] is normal. It’s not.”

At first glance, police figures suggest that San Francisco is solving homicides quickly. The SFPD in 2024 had a 94 percent clearance rate for homicides, well beyond the statewide average of 64 percent. But clearing a homicide only means someone has been arrested, not convicted, and it’s certainly not a guarantee that the murder has been solved given that all defendants are innocent until proven guilty. In the San Francisco Superior Court, more than half of homicide cases are still open after six years.

Asked to comment on the long-stay population, the San Francisco District Attorney’s office placed the blame entirely on defendants and their attorneys. “The prosecution is not responsible for these extraordinary case delays and would not legally be able to delay a trial this long,” wrote SFDA spokesperson Randolph Quezada. “The benefits to defense delays aren’t new — hence the old saying: ‘Delay is halfway to acquittal.’”

“I’m still sitting here. I’m innocent.”

Twelve people have been in pretrial detention in San Francisco for at least nine years. Two of them, Marquez Harrison and LaCarla Carr, were arrested in December 2014 in connection to the killing of a 23-year-old man named Da’ron Raynaldo and burglaries and robberies.

There has never been a trial and they remain in jail. During an interview in July 2025, Harrison said his court hearings were getting repeatedly re-scheduled by the DA with the judge’s approval. “It seems like it’s already scheduled before I get there. They just repeat it. That’s it,” he told me.

“When you think about it, if a person is guilty, the DAs normally want to go to trial, right? But I’m still sitting here. I'm innocent. So that's how I look at it, like why wouldn't I want to go [to trial]? But I've been sitting here," he said. Carr did not respond to a letter I wrote to her, and when I showed up for a visit, a deputy said she was declining to meet with me.

“We did not and could not delay a case for 11 years,” the SFDA spokesperson responded. “Mr. Harrison, like every defendant, had the right to assert his speedy trial right from the inception of this case. Only he knows why he did not do so from the start.

According to court documents, Harrison asserted his speedy trial rights half a dozen times over the years, starting back in October 2015. In February 2022, both sides said they were ready for trial, but there were no courtrooms available, with court documents citing Covid-19 as the reason.

Recent court hearings support Harrison’s version of events.

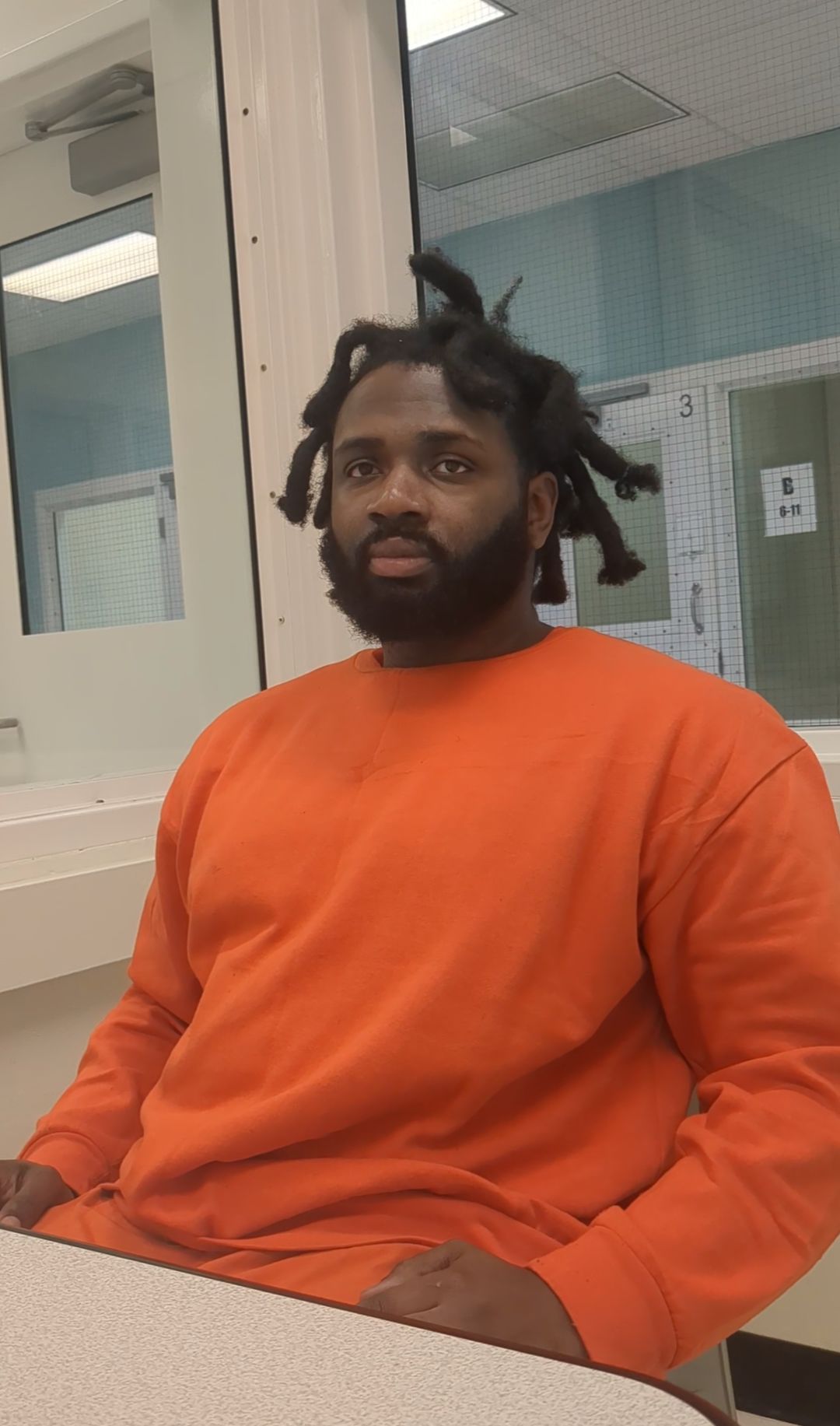

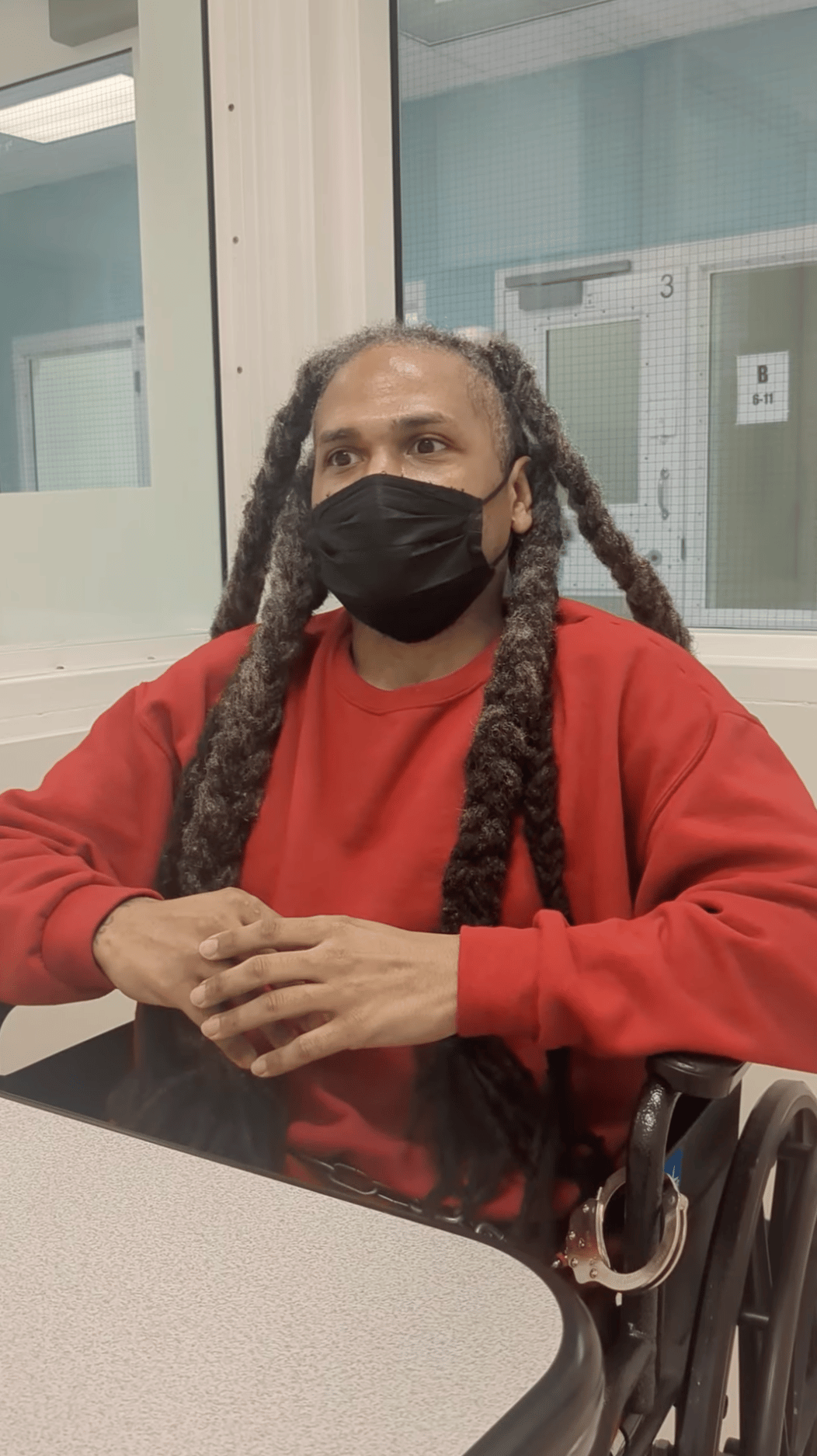

Marquez Harrison in July 2025. Photo by Amy Martyn.

On November 5, 2025, Harrison and Carr had a hearing in front of Judge Teresa Caffese, who is in charge of the court’s calendar, a duty that includes making sure cases don’t get delayed excessively. At the start of the hearing, Assistant District Attorney Ryan King asked for a continuance, the legal term for delaying a trial. The prosecutor said he was busy with another trial, and one of the jurors had to be replaced. “They’re all but starting over.”

"I would object to any further continuances," said Harrison’s court-appointed attorney Marsanne Weese, the fourth court-appointed attorney he has had, who has been representing him since February 2024. After Weese became his lawyer, Harrison asserted his speedy trial rights in May 2025. Weese was ready for the trial by August. Harrison “has been in jail for more than 10 years,” Weese reminded the judge.

The judge didn’t seem bothered to hear that Harrison has been locked up for more than a decade. She quickly ruled in favor of the prosecutor. The case was continued.

Later that month, Harrison and Carr had their next court hearing. The lead prosecutor did not show up. “Mr. King is currently engaged in another homicide trial, so we are asking to continue this trial,” said the prosecutor appearing on his behalf.

Harrison’s attorney objected again, pointing out that King was now busy with a different trial than the one he was busy with last time. “The prosecution chose another defendant over my client,” she said.

The judge decided that the prosecutors had "good cause.” Case continued.

The next hearing was on December 12. This time, Harrison’s co-defendant Carr and her public defender Rebecca Young were not there. Another attorney said that Young had a family emergency. Carr and Harrison can’t have separate trials because the DA’s office is insisting that they be tried together. The judge agreed to push the trial off yet again. Harrison’s attorney objected and filed a motion arguing that his constitutional rights are being violated.

The DA’s office are “the ones that are perpetuating this,” Harrison’s attorney told me.

Institutional and ideological reasons for slow pace

Just a few miles away from the AI billboards and the $1 billion phallic monument to sales sits the Hall of Justice, the decrepit building where San Francisco’s criminal hearings and trials take place. It was declared unsafe for earthquakes in 1996 and hasn’t been fixed. On a typical weekday there are about five hundred cases scheduled among roughly two dozen courtrooms, most of them for 9 a.m. It’s anyone's guess what time defendants will actually see a judge.

County Jail #2 and the walkway that connects it to the Hall of Justice. Photo by Amy Martyn.

In interviews, defense attorneys and court clerks described institutional problems in the San Francisco criminal justice system that could explain why cases take longer to close.

“We're in a situation now where the court had a hiring freeze, and the criminal courthouse has got a volume right now that I don't think has ever been seen,” said Rob Borders, a deputy clerk with the Superior Court of San Francisco. The court administration “is not making any kind of adjustments as far as, let's commit more resources over there.”

The Superior Court of San Francisco declined to comment.

Another defense attorney speaking anonymously told me that their clients are sometimes kept waiting because there aren’t judges available to handle their trials. “I don’t know if it's a lack of judges and we just need more judges or if it's some kind of institutional function,” the attorney said.

Attorneys also point to the political climate under the current DA. “There is a very clear policy of this DA’s office doing everything they can to just keep people in boxes as long as they can,” said Brian Ford, a court-appointed defense attorney. Ford and other attorneys said it is difficult to get reasonable plea deals under the Jenkins administration. When negotiations stall, so do cases.

The SFDA spokesperson responded: “What we see is that the defense does not care about public safety and wants everyone released no matter how serious the crime and dangerous the offender.”

The people in jail I spoke to were conflicted about how much blame to place on their own attorneys for their cases languishing. Most defendants in San Francisco cannot afford a private lawyer. They are either assigned an employee from the Public Defender's office or a court-appointed attorney who is independently contracted by the county. Representatives from both groups of attorneys have recently testified about having too many cases. All nine people in jail a year or longer who I interviewed were represented by the court-appointed attorneys.

“It's fucking crazy how many cases these public defenders and these court-appointed attorneys get,” said Bell, who has been through a handful of different court-appointed attorneys over the years and briefly tried to represent himself.

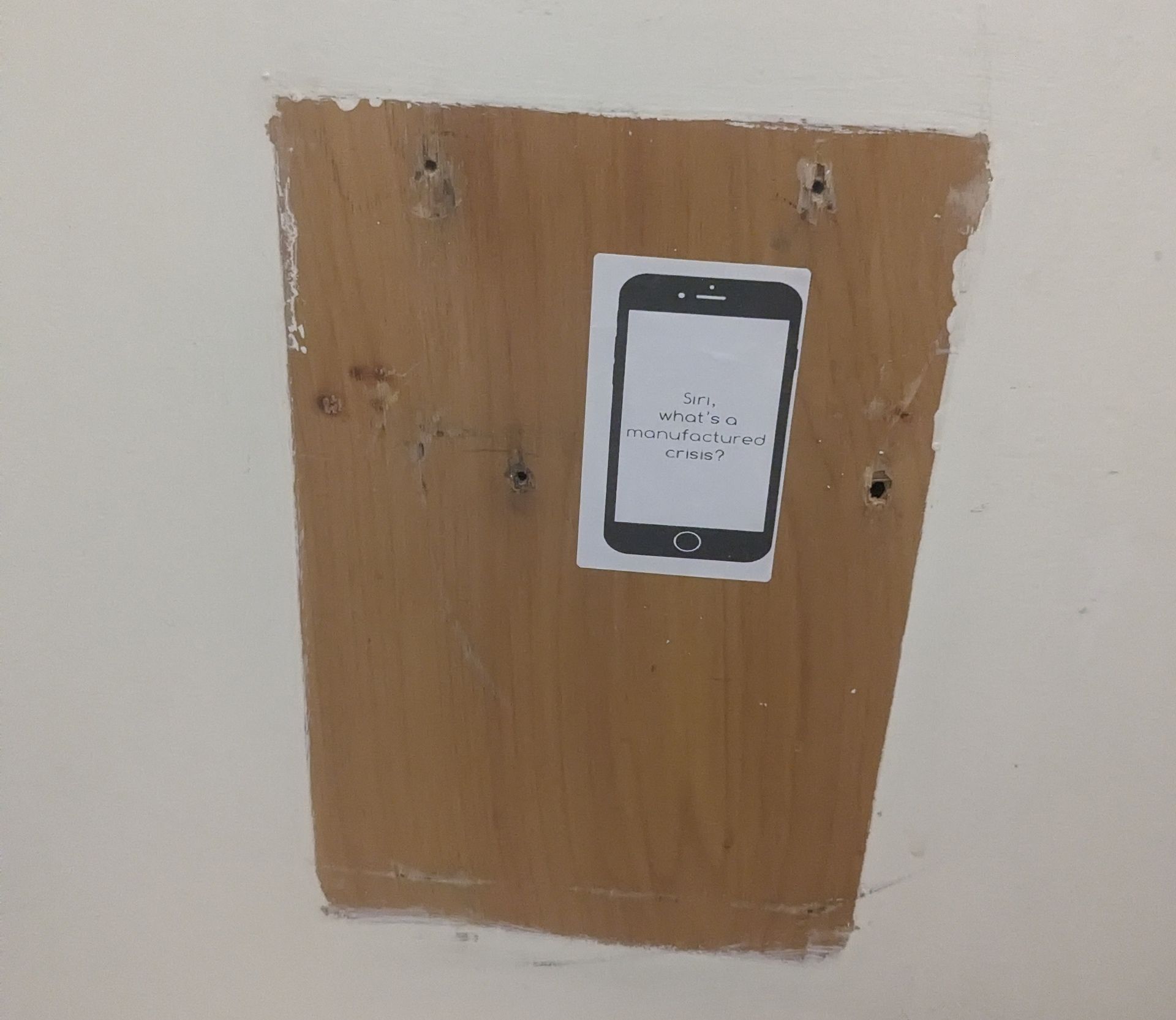

Social Commentary in a Hall of Justice bathroom stall. It says, “Siri, what’s a manufactured crisis?” Photo by Amy Martyn.

Harrison said that he did not want to criticize any of his previous attorneys. “They are trying to do the right thing. So you don't ever want to rush them,” he said. “They are definitely overworked too.”

“The bottom line is we are not clearing cases,” said attorney Julie Traun, who is in charge of the program for county-appointed lawyers, at a special hearing about defense attorney workloads. “We are not resolving them.”

Defense lawyers for people who can't afford to pay have vastly less resources than the prosecutors and the police. The San Francisco Public Defender’s budget was around $56 million in the last fiscal year, while the DA had a budget of $93 million. The police department’s budget was $882 million. “There's no parity between the Public Defender and the Prosecutor's office,” San Francisco Public Defender Mano Raju has said.

When Americans think of pretrial detention that lasts years, they often think of New York City’s Rikers Island. The jails in New York City have a total of 204 people who have been there for three years or more, according to figures obtained from a public records request. That’s more than twice as high as San Francisco. But the population of New York City as a whole is 8.4 million people–nearly ten times the county of San Francisco. And New York jails don’t have any unsentenced inmates who have been there for nine years.

A decade of motions, lawsuits and jail

A year and a half after Reid died from a gunshot wound in the “bound and gagged” case, a grand jury convened to decide whether Bell and Brackens should be indicted. Court documents described Bell as the ringleader of a group of women who scammed Nordstrom with fake gift cards and engaged in sex work. One key witness was a woman who prosecutors said was part of Bell’s “family” who stole from Nordstrom. The woman said that Bell ordered the group to tie up the victims before they were allegedly placed in a car with Brackens.

But the woman gave that testimony without getting a chance to consult with the private lawyer she had hired. Instead, prosecutors sent police to her address, had her arrested, and then assigned her a different defense attorney that she met that day. Her original attorney eventually stormed into the courtroom in the middle of the grand jury hearing to ask what was going on.

“It was highly unusual,” the original attorney named Tony Tamburello told me. “I finally figured out where she was, and I went to the court, and the court made rulings, but couldn't do anything about the fact that the grand jury already heard her testimony.”

Vincent Bell in July 2025. Photo by Amy Martyn.

Bell filed a motion for prosecutorial misconduct on the basis of that and has repeatedly challenged evidence and accused prosecutors of corruption. One of the former prosecutors, Eric Fleming, is now a judge in the same courthouse. Harry Dorfman was also a prosecutor early in the case and is now a judge. (The San Francisco Superior Court declined to comment on their behalf. The court says that judges are not allowed to comment on open cases).

Bell lost one leg from a shooting a few years before he was arrested and uses a wheelchair in jail. Being in administrative segregation means he is in a cell for twenty three and a half hours everyday. He has several lawsuits describing abuse at the hands of deputies. He once made national news as the “One-legged inmate awarded $504K in excessive force suit.”

Other long-stayers, including Brackens and Harrison, are also part of lawsuits describing inhumane conditions and abuse. Harrison said he has gained eighty pounds over the course of his pretrial detention because of the lack of time outside. Brackens has testified about the effects of not getting any sunlight for years and nearly dying from diabetes while in jail. At the same time, Brackens told me that being in jail saved his life, because it forced him away from his old mindset and choices. “I offer the world so much more than what I was giving it. So me having to sit down, I realized that, Brackens said.

For Bell, isolation is “horrible in a sense that, you're basically fighting a battle against yourself to see how mentally strong you are, on how to handle being locked in a cell for so long…And at the same time, I'm just like, this is just something that I've got to do in order to prove my innocence, so no matter how long it takes, I will sit and fight to prove that I'm innocent.”

The only source of light for inmates at SF County jails is these overhead lights. Photo by Amy Martyn.

During our interview in July, Bell seemed hopeful that his case would resolve soon. He had recently been assigned a new court-appointed attorney that he liked named Vincent Barrientos.

“Prison is probably a possibility. I may go home,” Bell said. “Even though I want to prove my innocence, if they offer me credit for time served to go home, then of course I'm going to take it.”

The recent court hearings for Vincent Bell and Montrail Brackens

Court minutes show that Bell has been consistently invoking his speedy trial rights since September 2024. The spokesperson for the prosecutor’s office responded that “most of the 13 years have been defense delay.”

It was an ordinary day in June 2025 when Bell and Brackens were brought into Judge Caffese’s department for another hearing. Bell had long grey dreadlocks and was shackled around the waist to his jail-issued wheelchair. He was dressed in red to signify that he was in administrative segregation. Brackens was in standard orange. They reached for each other’s hands and embraced with a hand shake in the brief moment they got to interact in the courtroom.

“How old is this case?” Judge Caffese asked.

“It’s from 2012,” said Assistant District Attorney Dane Reinstedt.

The judge asked the prosecutor why the case had gone through so many different attorneys.

“It’s a complicated answer,” the prosecutor responded without elaborating.

Bell’s attorney said he wasn’t ready for the trial because he was new to the case and still reviewing evidence. The prosecutor agreed that the attorneys needed more time. “There is a large quantity of discovery, I think it’s reasonable that he needs more time to prepare,” the prosecutor said. Within a few minutes, the court hearing was over.

In November 2025, Bell and Brackens were brought back to Judge Caffese’s courtroom.

"This is on for trial. Are the people ready?" Judge Caffese asked.

"No," responded a different prosecutor, Assistant District Attorney Jordyn Sequeira. She said that the lead prosecutor on the case was now busy with another trial.

"We're asking to come back late January for setting a pretrial conference," said Brackens' court-appointed attorney Paul Dennison.

San Francisco County Jail #2. Photo by Amy Martyn.

Caffese gave the attorneys a few minutes to confirm their schedules. As everyone talked among themselves, Caffese turned to a court staffer and said, "We just do [indecipherable] on autopilot here." It was unclear what she was referring to. The Superior Court declined to comment on her behalf.

Bell and Brackens greeted each other again. Then they were brought back to the jail, to wait two months for another hearing, on the promise that maybe it would be the one where something would finally change.

Their next court date was on January 16, the Friday before a long weekend (Monday was a federal holiday), and a chaotic day in Judge Caffese's courtroom. Some defense attorneys seemed to be learning at the last minute that their clients in jail weren’t going to show up to their own hearings. The San Francisco Sheriff’s Department reported that 18 percent of inmates with court hearings had refused to leave jail to go to them. “It is kind of peculiar,” Judge Caffese said about the number of refusals.

When Brackens was brought out to the courtroom, his glasses appeared to be held together with masking tape. He was kept in handcuffs the whole time, with his hands at the front of his body, typically a sign that someone is facing disciplinary action at the jail. Bell was not there. Barrientos was skeptical that Bell refused to come.

“I'm told it's a refusal. I don't think that’s correct,” Bell’s attorney told the judge. A spokesperson for the San Francisco Sheriff’s Department responded to me via email: “Vincent Bell did indeed refuse to go to court today. He’s been in our custody for 12 years; we don’t force anyone to go to court who doesn’t want to go.”

On the agenda was a new motion to dismiss the case that Bell’s attorney filed, arguing that the grand jury didn’t hear important evidence. Barrientos said he was ready to argue the motion and was also ready for a trial. But the prosecutor Dane Reinstedt said he needed to delay the case because he was yet again busy with another trial. The judge unceremoniously granted the prosecutor’s request.

The lawyers agreed to meet again by early February. They just didn’t know what date to choose. Court staff struggled to find a time that would work for everyone. A little before noon, a court staffer was still waiting for an email back from another courtroom to finish scheduling the next hearing for Bell and Brackens. “We’re going to have to pass this,” the court staffer said. “It might take awhile.”

Amy Martyn is a freelance writer and journalist in the Bay Area. You can find her Substack right here and email her at [email protected]