by Eunice Ross

During the pandemic, I visited Claude almost every week. While the world changed a lot around us, particularly in 2020 and 2021, he remained steady, calm, and unaffected by it all. Week after week, he looked the same and didn’t seem to age. His name made me think of a renowned chef trained in classic French techniques or an haute couture designer who makes custom clothes. I would spell his name with an accent mark like Claudé. I later discovered that Claude actually had an alligator companion named Bonnie who originally joined him, but they didn't end up getting along so Bonnie was taken away. Their names were a nod to the infamous outlaws, Bonnie and Clyde. Claude is neither a chef nor a designer. He isn’t even human. He’s an albino alligator, one of the California Academy of Sciences’ most celebrated residents. The museum sits in San Francisco, half a mile from where I used to live, close enough that visiting him became routine.

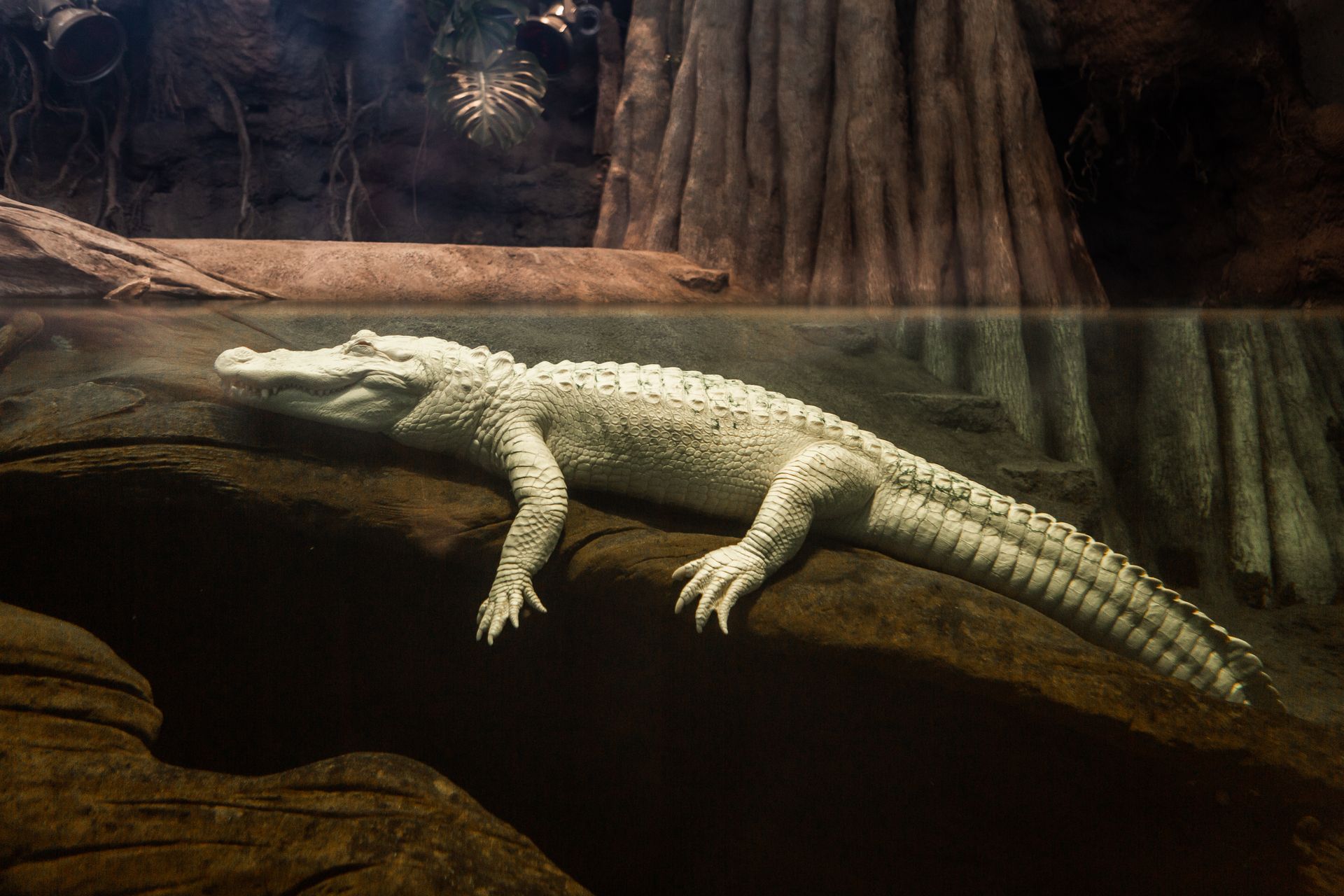

My first encounter with Claude was before I had children. I briefly glanced at him, settled in his indoor wetland with its woody plants, shrubs, and trees. What I remember most from that first visit was his appearance: Claude looked like a wax mannequin—fake yet lifelike. He had all the hallmarks of an alligator: the muscular, flattened tail, the ridged, armored spine, four stubby legs, and a blunt snout. But his coloring set him apart. His skin was a chalky white, almost powdery to the eye. They say the eyes are windows to the soul—if so, Claude’s were shuttered. Milky and pale, they revealed nothing, as if whatever lived behind them had long since disappeared.

When the lockdowns were lifted and the California Academy of Sciences reopened in 2021, I decided it was time to introduce my kids to Claude. With the virus still a threat, the museum limited attendance, but my membership gave us exclusive access to an early opening. Many mornings, my kids and I were the first visitors and the only ones in attendance for an hour or so. In these empty exhibits, separated by vast spaces, my daughter ran around as if in her own playground. My son stared at the penguins up close during feeding time. Here, there were no crowds to dodge. On these mornings, the museum felt hushed, sacred, and special. It was an intimate time, just us and the creatures – which, of course, included Claude. We greeted him the way you would a family member.

“Claude!” my daughter yelled, pointing excitedly his way.

Her voice echoed in the quiet room. My son gently curled his tiny fingers into a fist, wiggling them up and down in Claude's direction.

Photo of Claude courtesy of the California Academy of Sciences

I usually found Claude motionless, as if someone had just yelled, “Freeze!” The only proof he was alive was when I passed the viewing area again and saw that he had moved to another spot. It was as if an unseen mechanism was lifting him and placing him in different swamp areas every five minutes.

One day, we actually saw Claude moving; he crawled around the swamp more times than I’d ever seen him do before. I glanced at the other visitors, but no one was as excited as I was. My children gave Claude a full two seconds of their attention before going back to playing on the stairs and benches.

As I watched Claude, I realized that loneliness is a human emotion and that Claude was incapable of feeling it. I couldn’t help thinking that the white alligator shared my sense of isolation. So, as I gazed at him that day, it was hard not to feel that we shared similar emotions, each confined by circumstances beyond our control. What would Claude think of me, I wondered, a stranger so invested in his emotional state. Watching him, my thoughts drifting, I imagined what would happen if I leaned too far over the railing and accidentally fell into the swamp. As the scenario in my mind unfolded, I saw myself bouncing off the net and landing on my stomach in the rock area. Stunned, I slowly push myself up on my hands and knees, and find myself face-to-face with Claude: two lonely beings isolated from their natural environments. Each of us enduring some kind of captivity. Then, I remembered who we truly are. I took a step back from the rail and looked around for my kids. I am a human, I reminded myself. And Claude is a reptile.

Four years have passed since then, and in June, Claude turned thirty and was more popular than ever, always surrounded by crowds—all the people who had been absent during those many mornings when I communed with him alone. When I saw him in recent years, I remained conscious of the same empathy and solidarity I felt during those pandemic days, but I no longer felt it as vividly, as immediately, as I did then. Claude's alienation, however—whether he was conscious of it, as I once imagined, or indifferent—remained unchanged. I still felt a connection, traces of that pandemic kinship, but the emotion had faded. Time and normal life had softened it.

So the sadness I felt upon hearing about his passing caught me off guard. It was like mourning someone I knew deeply. He was an alligator. Still, the loss is real. Like many in the Bay Area, my children loved visiting him, reading the book about him we found at the museum gift shop, and snuggling with the plush version we bought. And for me, I'll carry those isolated mornings—the peculiar friendship we forged when the world had narrowed to almost nothing.

Eunice Ross is a writer whose work has been featured in the New York Times, Refinery29, MOTHER, and Goodreads. Born in the Philippines and raised in the Bay Area, she currently lives in Oakland with her partner, their kids, and a golden retriever.