There is no such thing as a Native San Franciscan, yet everyone born and raised here says they are. I understand. It must be quite a gift, growing up here. And I doubt they mean “Native” in the Indigenous sense. Few (if any) could. The real SF Natives were imprisoned, enslaved, infected, assaulted, slaughtered, and buried beneath the city we live and work in.

I am Indigenous, though not to San Francisco or even California. My tribe, the Potawatomi, were displaced to make way for the city of Chicago. This is not my origin story, though I don’t need to descend from SF’s first peoples to tell you that every square inch of the United States is Native country. This is not my origin story, though I can sure as hell relate.

This is Ohlone land

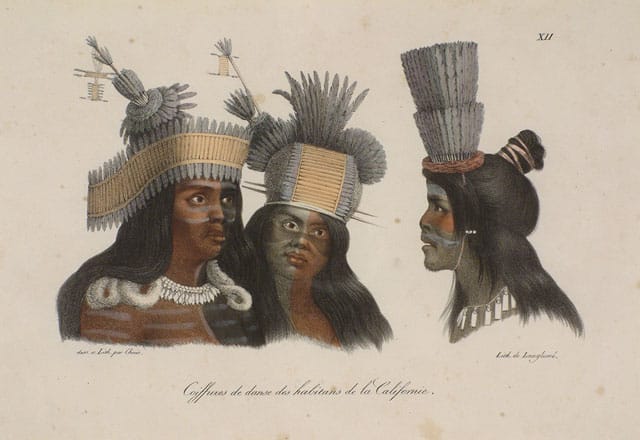

You may have heard that the Bay Area belongs to the Ohlone people. They would tell you it’s the other way around. And you might not recognize their name like you would the Iroquois, Navajo, Sioux (all settler-given titles, by the way). The Spanish colonized the Bay Area in ways that rival Andrew Jackon’s anti-Native sadism. It’s a miracle the Ohlone survived at all.

“Dogs of the conquest, who had already acquired a taste for human flesh (and were frequently fed live Indians when other food was unavailable), were the colonizer’s weapon of mass destruction. In his history of the relationship between dogs and men, Stanley Coren explains just how efficient these weapons were: ‘The mastiffs of that era . . . could weigh 250 pounds and stand nearly three feet at the shoulder. Their massive jaws could crush bones even through leather armor. The greyhounds of that period, meanwhile, could be over one hundred pounds and thirty inches at the shoulder. These lighter dogs could outrun any man, and their slashing attack could easily disembowel a person in a matter of seconds.’”

— Deborah Miranda (Ohlone-Costanoan Esselen Nation, Chumash), “Extermination of the Joyas: Gendercide in Spanish California” (2010)

“Ohlone” serves as an umbrella term for Bay Area tribes united under one language family, with six respective dialects. North of San Pablo Bay in modern Marin County live the Coast Miwok; neighbors, though linguistically unrelated. The Southern Patwin, a Wintu band (also no relation), still live on their homeland north of the Carquinez Strait. Carquin is Spanish for Karkin, after the Karkin Ohlone who call the strait home. South along the Bay and down the coast to Carmel is all Ohlone territory, including San Francisco.

San Francisco is Yelamu territory

On the Peninsula live the Ramai, an Ohlone band. San Francisco hosted a Ramai tribelet we call the Yelamu. “[Dr.] Randall Milliken, an expert on the Yelamu and author of an authoritative study of the destruction of Bay Area Indian culture, A Time of Little Choice: The Disintegration of Tribal Culture in the San Francisco Bay Area, 1769-1810, estimates that San Francisco’s population was between 160 and 300 people at European contact.” (foundsf.org)

Bay Area historian and writer James Benney calls this a gross underestimation. In his research, approximately 1,500 Ramai people, including the Yelamu, occupied the peninsula including San Francisco. “But by the end of the Mission Period, only a few families had survived,” he published in his 2020 blogpost. “For every one hundred Natives incorporated into the California missions, over 75 died a premature death. Average life expectancy after baptism was only nine years, and at Mission Dolores in San Francisco it was only 4.5 years.”

San Francisco was a wild, wind-whipped, shapeshifting sandscape before colonization. Bayside coves sheltered salty marshland and the people who thrived off its food sources. Chasing good weather, the Yelamu moved about proto-San Francisco like today’s residents hopping from one microclimate to another. The village of Petlenuc sprang up around a rare freshwater spring until the Presidio fenced it in, nearly destroying it. The real threat hadn’t even reared its ugly head.

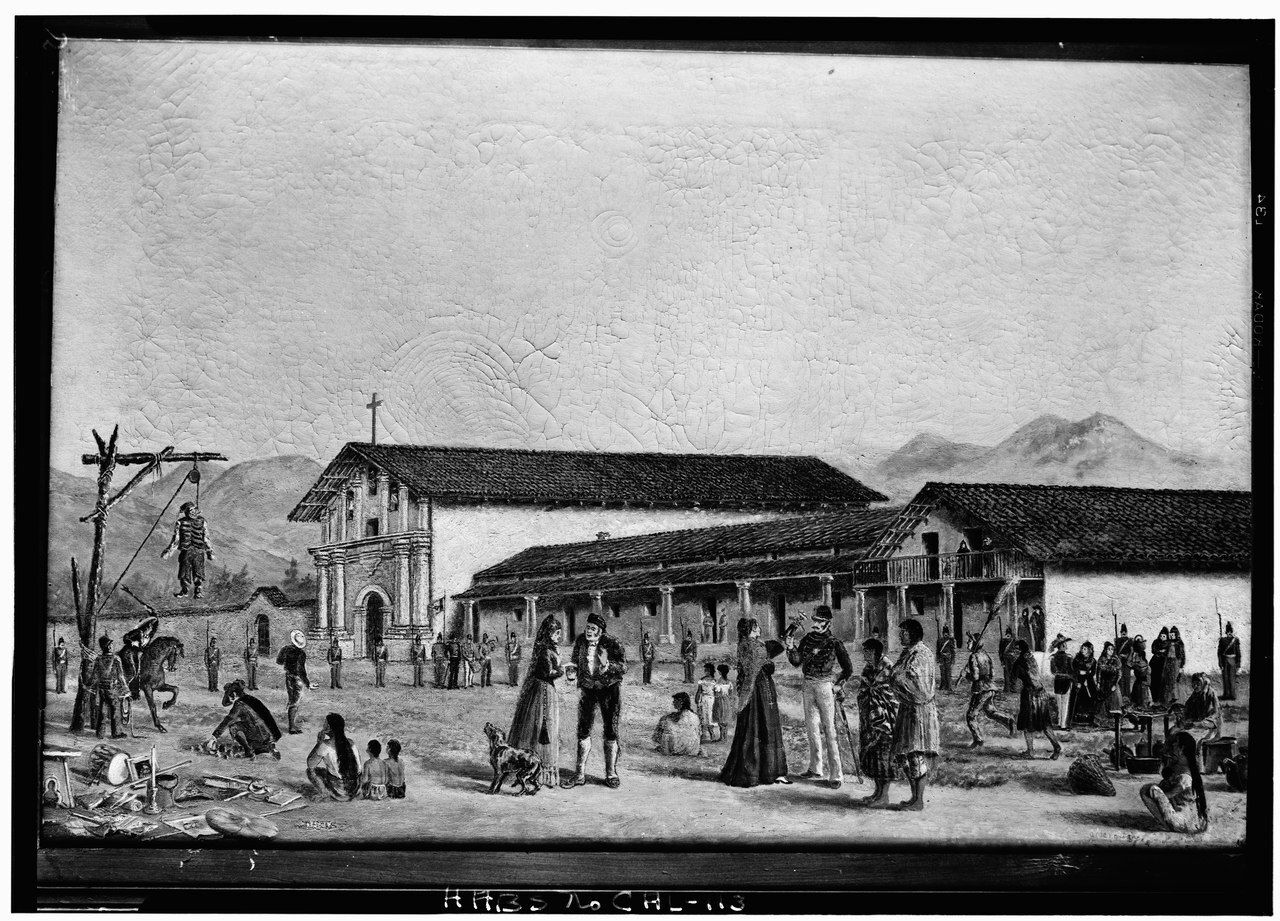

The beginning of the end

The beginning of the end started in 1776, when the first mission was built a thousand or so feet south of today’s church. By the following year, missionaries had fed and clothed enough Yelamu converts, called “neophytes,” they could extract labor from them. The new chapel would weather fire and earthquake because the Yelamu were forced to construct walls four feet thick. Finished in 1791, Mission Dolores tore a hole in the fabric of Indigenous space and time. Dragged into the inescapable darkness first were the Yelamu Ohlone.

“All Native people recorded by missionaries as coming from the San Francisco Peninsula were baptized and indoctrinated into the mission system by 1801.” (San Francisco Estuary Institute) With the Yelamu depleted, the mission pursued the nearby Ramai. Mission Dolores also reaped Karkin, Chochenyo, and Taimen Ohlone from across the Bay, as well as Coast and Bay Miwok, Patwin, Pomo, and Wappo prisoners. The Misión San Francisco de Asís detained an estimated 1,100 Bay Area Natives at its height.

They expanded their reach well beyond their whitewashed adobe walls because the Indians they captured kept dying. “Due to disease, overcrowding, malnourishment, and poor conditions, these native peoples died at rapid rates…by 1842, only 15 persons native to the SF Peninsula were still living at Mission Dolores.” (SFEI)

The Indigenous death rate at Mission Dolores soared throughout the early 19th century. Mission San Rafael Arcángel (Marin County, 1817) accommodated extra and ailing Natives from Dolores, as did Mission San José. Dolores continued operating for more than a decade after the Mexican Secularization Act of 1833, if in diminished capacity. The Franciscans finally relinquished control in 1857, handing possession to the archdiocese of San Francisco, but the damage was done. An 1852 estimate claims 5,387 Natives lay buried in and around Mission Dolores.

Aftermath

These are details you weren’t meant to see, and that was intentional. This is the history to which ours is Other. If you grew up in California, you were literally taught wrong. “The use of rhetorical devices (like the passive voice so prevalent in missionization histories: ‘The Missions were built using adobe bricks’ rather than ‘Indians, often held captive and/or punished by flogging, built the Missions without compensation’).” (Miranda, 2010).

Sounds like Padre Jayme fucked around and found out. This screenshot’s from yesterday, by the way.

The assassination of the Ohlone continued into the 20th century. Director of the Hearst Museum of Anthropology Alfred Kroeber concluded the Ohlone were extinct, costing the tribe vital federal recognition. The Ohlone have been fighting tirelessly to restore their status ever since. Surviving Ohlone families are mostly Tamien, Chochenyo, and Mutsun. On the Peninsula, “just one lineage [of the Ramai] is known to have survived. Their descendants comprise the four branches of the Ramaytush peoples today.” (Dr. Jonathan Cordero)

It appears the closer you get to Mission Dolores, the fewer representatives of the land’s original inhabitants you find. There’s an infinitesimal chance that some Ohlone descendants are related to the Yelamu interred at Mission Dolores, but we just don’t know. That is why fascinating tools like native-land.ca confer San Francisco their nearest relatives, the Ramai, or Ramaytush Ohlone. There are no known living Yelamu descendants.

So when you hear some pithy land acknowledgment stuttered out to a woefully mispronounced Ramaytush Ohlone, remember that tribe will hear it on behalf of their relatives who didn’t live to carry out their own legacy. There’s no such thing as a Native San Franciscan. Not anymore. That should be the Yelamu, and they deserve to be remembered.

That said, plenty of Bay Area Natives exist here now, and are more than deserving of your support. If you live in SF like myself or somewhere along the Peninsula, please consider donating to the Ramaytush Ohlone as they continue to defend their right to exist. For my East Bay and Contra Costa friends, please consider donating to the Lisjan Ohlone as they fight to regain their homeland. Give thanks to the Native land you live on. I think it’s only fair.