Marathon rains have held California’s attention these past couple weeks. Meanwhile in the San Ramon Valley, the Earth won’t stop rumbling. It’s got pets and people equally riled up, losing sleep. Hardly a day goes by without a noticeable tremor. Some were even felt in San Francisco. This deceptively unprecedented activity does not mean faults are letting off steam nor winding up for a Big One. In one respect, this is simply part of life in California, and we should expect the occasional tremor. But earthquakes have rattled San Ramon for at least a month now, and many residents want to know why.

Bay Area geology made easy

Here I’ll assume you paid attention in science class and skip Plate Tectonics 101. You’re smart enough to understand how the San Andreas Fault works already. While a majority of diagrams depict the plates making a clean-swiping, just-gonna-scootch-right-past-ya motion, the tectonic car crash on which we live is not head-on. It’s more like the North American Plate t-boned the Pacific. It’s bent out of shape near LA, but being the denser plate, it meant the North American’s entire front end crumpled. In the Bay Area, we hear far more from faults east of the San Andreas than west of it. Wherever you see mountains in California, earthquakes (sometimes, volcanoes) are responsible.

The rate at which the plates grind past each other is inconsistent. The USGS estimates about 2” a year. While the San Andreas is designated plate boundary, more earthquakes occur within the general fault zone than on the fault itself. The whole Bay Area rests atop the San Andreas Fault System, of which the Calaveras Fault is part. Its northernmost strand runs immediately west of San Ramon; due east, the lesser-known Pleasanton Fault. They pinch the valley floor, warping it downward, allowing fertile sediments to pool and level out for millions of years.

North-northeast of Danville and San Ramon, watching over the Inland East Bay, Mount Diablo is key to this process. You know when somebody’s “thrown a wrench in the works?” That’s a quick and dirty version of what’s happening here. Mount Diablo is wedged between the northern tip of the Calaveras Fault and the southern end of the Concord Fault.

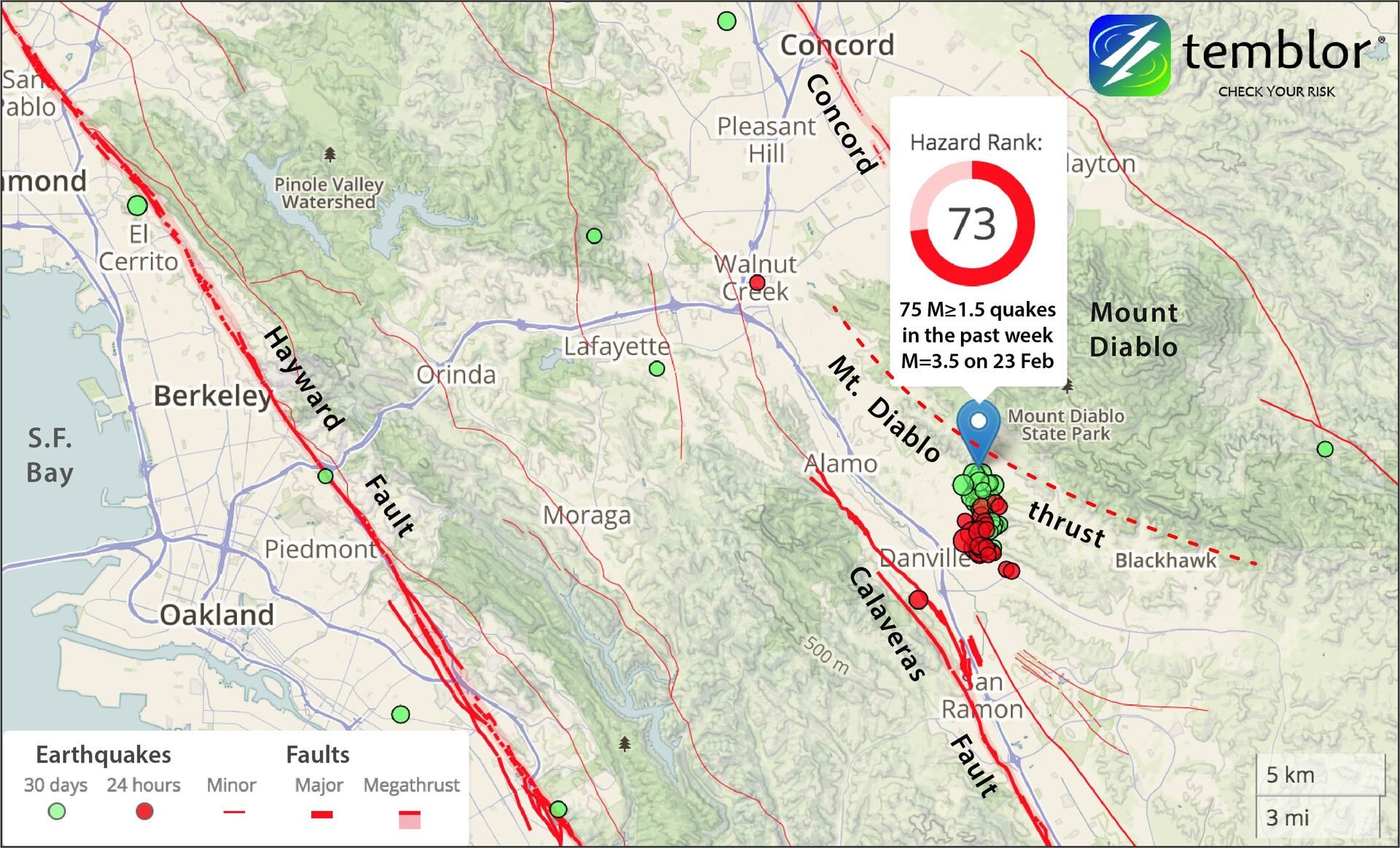

This map from temblor.net shows the earthquake swarm of 2018. The Hazard Rank sign is partially obscuring the Concord Fault marker.

See how the Calaveras Fault peters out west of Mount Diablo, but the Concord Fault begins just north of it? The faults are literally squeezing the mountain upward, about five millimeters a year. On its southeast flanks, an active thrust fault named for the mountain accommodates some of this tension. While Mount Diablo is its own respective entity, the generative phenomenon is what seismologists call a stepover.

Step on over

A stepover happens where two strike-slip faults (the Bay Area’s predominant type) almost meet, like trapeze artists that barely miss. But if the Calaveras and Concord Faults are squeezing Mt. Diablo, why does San Ramon keep shaking? It’s because the region encompassing the mountain transmits tons of seismic stress between fault termini. The crust between faults is subject to so much strain, it is thoroughly crosshatched with cracks. Stress routinely steps over the cracks like it’s crossing a rope bridge over a ravine.

Faults in the Bay Area and Central Coast regions of California exhibit a rare phenomenon called creep. TLC may or may not have named their 1994 hit song after it. It describes movement along a fault significantly faster than expected that doesn’t cause earthquakes. The Calaveras creeps right along at almost 1.5” a year near Hollister, where it branches off the San Andreas. Evidence can be found about town: sidewalks cracked and yanked apart, retaining walls split and pulled in different directions. But like groceries piling up on the conveyer belt, that movement piles lots of strain on the northern end of the Calaveras—right beside San Ramon.

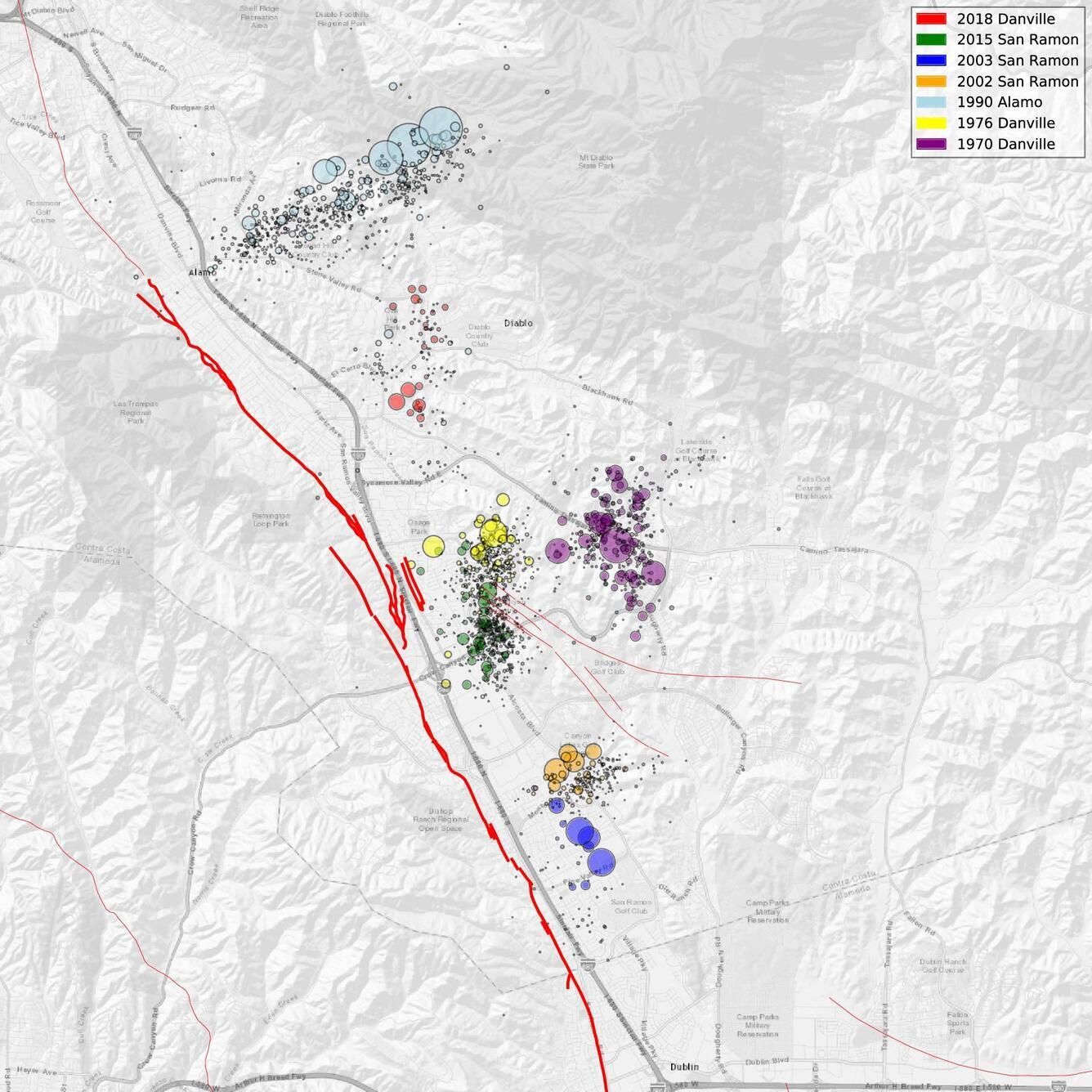

Earthquake swarms happen more often that you think. Take a look at this image courtesy of the USGS. Since the 1970s, seven swarms have occurred in the region. The current marks the eighth. Calaveras Fault in red.

A stepover is not hazardous. That web of cracks cannot yield shaking much stronger than a M5.0. If anything, it benefits human civilization by handling seismic stress like a bucket brigade from one creeping fault to another. That is why this swarm, although geologically interesting, is not a portent of disaster. However, unlike its racy southern half, the northern Calaveras is locked with enough firepower for a M6.0+ earthquake. But even I wouldn’t lose sleep over this scenario. The Calaveras Fault is less likely (26%) to host a M6.0+ than the Hayward Fault (33%); are you ready for that?