Could a Housing Bill Fight Segregation in San Francisco?

Senator Scott Wiener recently announced Senate Bill 827, which would enable denser housing construction around major transit stations and frequently used bus stops.

Most California communities limit the number of Californians who can live near public transportation through low-density zoning. SB 827 is a major blow to low-density zoning, which reinforces long-standing racial housing segregation while exacerbating displacement, income inequality, and hampering economic growth.

What is low-density zoning?

Until 1968, the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) enforced an explicit policy of racial discrimination in mortgage lending. Under redlining, one black family was all it took for the FHA to demarcate a neighborhood as “undesirable” and refuse to guarantee loans for nearby houses. It incentivized homeowners to deed-restrict the sale of houses to white families only, creating all-white neighborhoods. White families sought to expel racial minorities in their neighborhoods by threatening black families with burning crosses.

The Fair Housing Act banned explicit racial discrimination in housing like race-based deed restrictions and redlining. But it did not ban density limits which resulted in race-based housing segregation.

White homeowners were still loathe to share their schools, parks, and roads with black families, so after the Fair Housing Act, cities around the country began implementing low-density zoning in order to ensure that black families could not afford to live in their communities. Race-based rules were replaced by land use regulations mandating single-family homes, minimum setbacks, minimum lot sizes, and parking requirements. For example, Milpitas banned apartment buildings after 250 black residents moved in to work at an auto manufacturing plant.

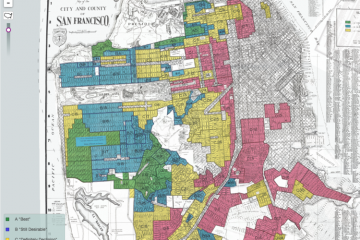

To see the impact of zoning on the racial distribution of a city, compare a map of San Francisco’s redlining map to its zoning laws to its current racial housing segregation.

Here’s a redlining map created by the Home Owners Loan Corporation in the late 1930s.

Source of the map here.

The New Deal agency authors described B15, in the Sunset, as a “Still Desirable” area to live.

“There are no racial concentrations, and the threat of infiltration of this character is remote.”

They labeled Forest Hill “Best,” and wrote that it was protected by deed restrictions ensuring that no homes could be sold to black families, and “zoning to single-family residences only.”

The current zoning map of San Francisco might not reference racial concentrations or threats of infiltration, but looks remarkably similar.

Source of the map here.

And they both bear a more-than-passing resemblance to a map of San Francisco’s racial housing segregation:

Source of the map here.

What you’ll notice is San Francisco has zoned the areas with the highest concentrations of white and Asian American residents for the lowest density.

Zoning also exacerbates income inequality among People of Color by geographically concentrating wealth and poverty. The median white homeowner’s house is worth $85,800 compared to $50,000 for black homeowners and $48,000 for Latino homeowners. That disparity mostly arises from the difference between home values in white neighborhoods versus non-white neighborhoods.

Beyond a net worth bolstered by housing price appreciation, a household’s location determines the quality of their transportation, job opportunities, health care, and educational opportunities. For example, The New York Times reports that increasing access to public transit is crucial to alleviating poverty.

“More than 20 years of research has implicated residential segregation in virtually every aspect of racial inequality, from higher unemployment rates for African Americans, to poorer health care, to elevated infant mortality rates and, most of all, to inferior schools,” writes 2017 MacArthur fellow Nikole Hannah-Jones.

Low-density zoning insulates wealthier neighborhoods from new construction. Luxury housing ends up displacing San Francisco’s long-time black and Latino residents because majority white and Asian neighborhoods aren’t zoned for apartments and condos.

Low-density restrictions also raises the cost of housing, and has played a part in San Francisco’s skyrocketing housing costs. The city is covered by vast swaths of land zoned for single-family homes with two-car garages. This leaves teachers, retail workers, first responders, and other middle-income professionals who can’t afford a single-family home facing two-and-a-half-hour commutes or living in their cars.

More density is the solution

SB 827 would help people of all income levels to be able live near transit. It promotes racial justice by preempting low-density “snob” zoning in wealthy suburbs with strong transit access.

t would also help ease the disproportionate burden for building currently on low-income POC communities by encouraging multi-unit construction in low-density wealthy white neighborhoods. Zoning for density makes building new homes in place of single-family homes more cost-effective replacing existing apartments.

The Boston Globe says SB 827 maybe “the greatest strike against inequality that anyone’s proposed in the United States in decades.”

Low-density zoning exacerbates racial housing segregation, displacement, and income inequality. It was developed for the purpose of exclusion, and it’s still having that effect today. Striking mandates requiring the land around transit be used only for single-family homes with large front yards and parking spots is just common-sense. But it also helps move San Francisco away from our history of race-based housing patterns and toward becoming a more equitable, inclusive city.

This post originally appeared at the Bay City Beacon.