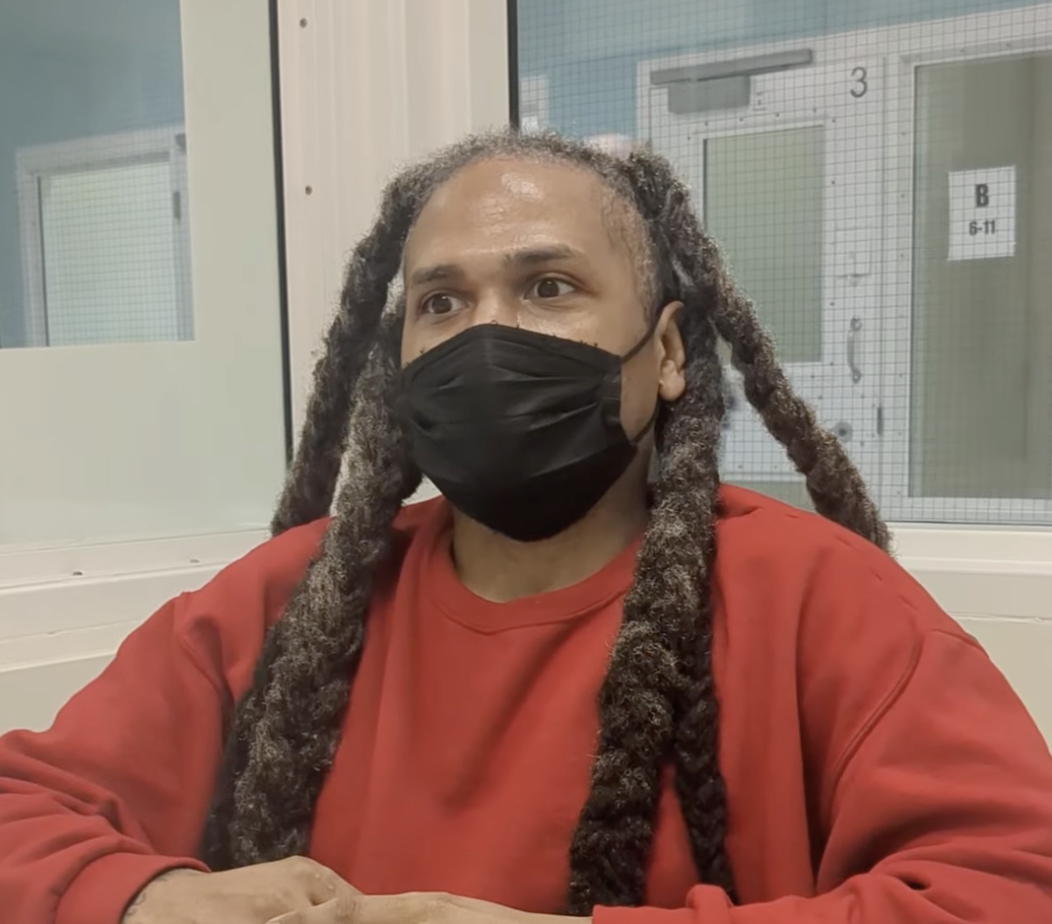

image from Everyday Feminism

Guest post by Sarah Dardick, Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist

Social Work and Counseling Master’s students typically spend two to four challenging years in graduate school. During this period of study, students are referred to as “trainees” or “interns” and are required to complete one or two full years in practicum providing therapy, almost always for free, under the tutelage of a supervisor in a community agency or school. Interns must commit 12 to 30 hours a week to practicum work which must be completed concurrently with Master’s coursework. The required time commitment for coursework and practicum leaves little, if any, room for paid employment for most students. Many are forced to quit their jobs and rely on some combination of savings and student loans until they complete their practicum requirements.

One would think that this combination of grueling coursework and unpaid labor is a worthy sacrifice, and be inclined to believe that a world of opportunity, job fulfillment, and wealth awaits the recent graduate. Following registration with the Board of Behavioral Sciences (BBS), Master’s level clinicians are referred to as “Associates.” Associates share the expectation that a bright future is just around the corner. After all, many mental health providers research their future prospects before jumping into the field. Local labor statistics and informal surveys of counselors in private practice support the assumption that counselors have high levels of job satisfaction, a decent income, and security resulting from a high demand for services. However, many mental health workers do not make it to this point.

Associates are required to accrue 3000 supervised hours within a six year limit to be eligible to sit for their licensing exam. Once six years has elapsed, the first hours gained begin to drop off, no longer count, and must be re-accrued. Providers are not considered fully licensed until these hours are fulfilled and the clinician has obtained a passing score on their licensing exam. A mental health provider cannot practice independently until this process is completed.

Additional obstacles further complicate Associates’ ability to obtain hours. For example, Associate Marriage and Family Therapists must obtain 500 hours working with children, families, and/or couples. The number of positions that serve these specific groups is limited, and competition is brutal.

image from The Professional Councilor

The majority of local agencies – propelled by underfunding, a desire to maximize revenue, or simply awareness of Associates’ desperation to obtain hours within the six year limit – have made it a common practice to exploit their unlicensed clinical employees. Unless an Associate is extremelylucky, the type of exploitation typically falls into one of three categories:

Unpaid employment.Unpaid positions tend to attract Associates by offering a combination of specialized training, flexible work schedules, warmth and support, supervision, help transitioning into private practice, advertising, and other incentives. Clients served by these agencies tend to be high functioning and not regularly crisis-prone; many agencies using this model are fee for service, do not accept insurance, or are focused on a specific niche population. Sometimes clinicians in these positions will be paid (often a small commission, per client) after a grace period of 6-12 months. Occasionally, employers will offer a periodic “stipend” which is almost always less than minimum wage.

Paid-for positions.For a fee of hundreds or even thousands of dollars a month paid by the Associate, certain agencies will hire the Associate to work at their organization. In exchange, the organization may offer any combination of training, supervision, office space, marketing, and permission to use the agency’s well-known name to attract clients. Associates are typically responsible for building their own caseload, and allowed to keep all or some of the hourly rate paid by the clients to whom they are providing therapy. This practice is almost always either illegal or not permitted by BBS. Agencies use loopholes and deceptive terminology, such as internship tuition or fee splitting, to disguise or mislead what actually occurs in practice. Associates who can afford this arrangement pursue it because it has the potential to set them up with a full caseload of high functioning clients once they are licensed and in private practice.

Paid employment. Clinicians in these positions are almost always considerablyunderpaid and earn an annual income that falls far below the San Francisco Bay Area median income. Clinicians who are fortunate enough to land a paid position pay for it in other ways. Clinicians in these positions typically provide case management (and, less often, therapy) to San Francisco’s most severely mentally ill and vulnerable. The burn out rate in these positions is extremely high, and many clinicians develop mental health conditions of their own due to the constant exposure to trauma, lack of access to personal care, and struggles associated with trying to survive on a low income. Self-care is paramount to all mental health workers and stressed as a necessity by seasoned clinicians, yet most Associates cannot afford their own therapy. If this were not bad enough, Associates are frequently asked to perform tasks that are out of scope and/or illegal to allow the agency to cut corners or save money. Illegal labor practices are rampant, with salaried employees consistently working unimaginably long hours and hourly employees asked to shift their time to the next business day when they accrue overtime. Sexual harassment from managers and supervisors is shockingly common in these settings and ranges from inappropriate physical/emotional boundary violations to quid pro quo arrangements to advance to coveted agency positions. Clinicians entering the field from these positions have often witnessed the modeling of low ethical standards for years. They may minimize the egregiousness of their actions which increases their risk of perpetuating poor ethical practices once licensed.

image from nbfe.net

Exam fees, annual associate registration with the BBS, initial license registration, professional organization membership, study materials, liability insurance, and other related professional costs can total hundreds of dollars a year – and this is not even accounting for student loan payments. These unavoidable expenses often create excessive financial hardships for associates already trying to live on a low income in the Bay Area. Paid employment is often the only viable option for most Associates, and the combination of disgracefully low compensation, stress, and exploitation forces many promising clinicians out of the field. Service jobs and positions with lower skill requirements provide much more compensation, making it exceedingly tempting for mental health workers to take solace in these roles prior to exiting the field entirely. Holding more than one job to increase income is impossible for many Associates who are raising families, coping with a disability, experiencing burnout, or who are simply rushing to complete their hour requirements on time.

This seldom mentioned glass ceiling is concealed to laypeople and those just entering the field of mental health. When questioned, the barrier is frequently dismissed as a rite of passage by those who, by privilege of their life circumstances, have succeeded in obtaining licensure. There is a subtle, implicit message that those who have obtained their license deserve it, and those who have not are somehow flawed, undeserving, or simply have not tried hard enough. This stopgap disproportionately affects first career earners, single parents, first generation college students, women, and individuals who represent specific ethnic/cultural minorities. This is especially shameful for a profession that professes its commitment to social justice.

Professional organizations have recently become superficially vocal about the struggle of pre-licensed clinicians, but no tangible change is being pursued and pre-licensed issues have not been made a priority. Professional listserves continue to advertise and endorse unpaid and paid-for positions, and professional organizations have done very little to increase participation from pre-licensed members. Associates struggle to afford membership to professional organizations, and receive very little in return if they decide to join. Some professional organizations have started to encourage Associates to participate in meetings, but they are almost always scheduled during the regular working hours of agency employees. Without representation, Associates are left with the responsibility of self-advocacy for improved working conditions. Despite being limited to blatantly unethical (and often illegal) means of obtaining pre-licensed hours, Associates do not report violations or seek legal recourse to obtain wages (which, in many cases, probably could be done) because they are desperate to quickly complete the 3000 hour requirement.

Recently, mental health workers from a handful of local organizations have gone on strike to highlight these injustices. While these strikes may achieve small gains, larger problems – ones that will demand significant time, commitment, and cooperation – still loom. Conditions as they stand do therapy a disservice, cheapening its value, exploiting future field members, obstructing the growth of talented clinicians, and ultimately harming clients. Mental health services are consistently undervalued, and deserve far more support and accolades than they currently receive. Manifesting that respect is an effort that needs to start from within, beginning with four cornerstones of change:

Lawmakers and the BBS must clarify the legal and ethical guidelines for Associate-specific work.

Agencies in violation of these expectations must be reliably and consistently penalized.

Post-BBS registration, Associates must be given clear information (and accompanying oversight / penalization) on acceptable-versus-unacceptable means of obtaining supervised hours.

Professional organizations and licensed practitioners must immediately discontinue normalizing unethical labor practices including unpaid work.

It is our duty as mental health professionals to implement policy changes that protect pre-licensed practitioners. Our value as professionals is intrinsically rooted in the value we place in one another, and that value suffers when we collectively normalize unpaid, exploitative labor. In short, complacency will continue the cycle of harm to future generations of pre-licensed clinicians.

Sarah Dardick is a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (#107221). She currently works for an agency that serves homeless adults in San Francisco. Her dream is to open a group private practice that has the capacity to provide an enriching, supportive, and decently paid position for a couple of Associates. She is an outspoken advocate for pre-licensed clinicians, an avid bibliophile, and loves striking up conversations with strangers.

The post The Labor Crisis Happening in the Bay Area’s Mental Health Profession appeared first on Broke-Ass Stuart's Website.