The Fight to Save Berkeley’s Alta Bates Hospital

By Nevin Long

A crowd numbering in the hundreds gathered in the atrium of the Ed Roberts Campus in South Berkeley on Saturday to discuss the fight against the closure of Alta Bates Hospital.

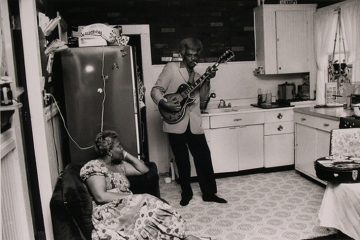

State Senator Nancy Skinner worries that closing Alta Bates might further stress an already overtaxed California public health system. Last year, she authored a bill which would have required the Attorney General of California to investigate non-profits operating in a fashion not in line with their tax status, but the legislation was vetoed by Governor Jerry Brown. Photo by Betty Rose Livingston

Officials from at least four municipalities, including Berkeley, Oakland, Albany and El Cerrito, and the state of California attended. Several, including Berkeley Mayor Jesse Arreguin and El Cerrito Mayor Pro Tem Rochelle Pardue-Okimoto, vocalized strong misgivings about the possibility that Sutter Health, Alta Bates’ parent company, could shutter the emergency room as early as the end of this year.

Sutter officials denied that they intended to close the hospital in a press release earlier this week. Chuck Prosper, chief executive officer of Alta Bates Summit, which manages the Herrick, Berkeley and Pill Hill campuses for Sutter, said in the statement that the not-for-profit corporation would provide “primary, specialty, and urgent care in Berkeley.”

State Assembly candidate Andy Katz, who sits on the Berkeley Health Commission, said that an urgent care facility would be insufficient for Berkeley’s healthcare needs. He said heart attack victims could be at risk should the emergency department cease operations, characterizing the potential move as “reckless.”

“You will not get a cardiac cath lab at an urgent care center,” he said.

Several of the speakers at the forum balked at the statement’s language, pointing out that keeping the acute care facilities, otherwise known as the emergency room, was not mentioned.

State Senator Nancy Skinner called the Sutter release “Orwellian.”

“It was completely unclear and full of obfuscation,” she said.

Skinner said she was concerned that Sutter was damaging an already vulnerable statewide public health system. She said, “California is rated F in terms of access to emergency rooms,” citing a recent report by the American College of Emergency Physicians.

‘Minutes matter’ was a popular refrain from the forum’s panel, who were concerned that a closure of the Berkeley emergency room could make the difference between life and death for serious emergencies originating along the I-80 corridor.

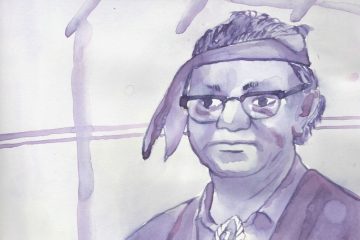

Doctor Ramona Tascoe, medical director of the Westside Methadone Treatment Program, argues against the potential closure of Alta Bates. Photo by Betty Rose Livingston

Kaiser Permanente in Richmond, the area’s only other comprehensive acute care center, contains 50 beds. In the event of a major disaster, such as an earthquake or fire, any overflow of patients would have to be transported to the Summit Campus in Oakland’s Pill Hill.

Berkeley Fire Chief Dave Brannigan said that his department shuttled 4,260 emergency patients to Alta Bates in 2017 with an average call time of 59.95 minutes, but trips to Summit were much longer. He said, “Transports to Summit averaged 70.08 minutes.”

“Additional factors will add time, so we’re projecting a 12-minute-per-call increase if Alta Bates hospital closes,” Brannigan said, “That’s about 924 hours of additional transports per year.”

Nuha Kalsay, an Associated Students of University of California, Berkeley senator, described one such incident. Last year, she had a severe allergic reaction that caused her to break out in hives. She called 911, but by the time help arrived her throat had begun swelling shut. She says her proximity to Alta Bates is what saved her life.

“If I hadn’t been able to get to Alta Bates in 5 to 10 minutes, I don’t know if I’d be here to tell you this story,” Kalsay said.

Locals have additional concerns. Most times, Berkeley resident Peni Hall can use her powered wheelchair to get herself to Alta Bates for treatment since she lives close by. Ambulances won’t transport her with her chair, which can be problematic in the case of an emergency.

“There’s just no way we can get anywhere else,” Hall said.

Peni Hall (left) and Maria Gil De Lamadrid live close enough to Alta Bates that they can use their powered wheelchairs to get themselves to the hospital in the case of an emergency. Should the facility close, they’d be forced to leave their chairs behind when an ambulance transports them to either Summit in Oakland or Kaiser in Richmond. Photo by Betty Rose Livinstong

On one occasion, she came down with a serious case of food poisoning outside the Berkeley Post Office. She was forced to call an ambulance, which meant leaving her chair behind along with many of her personal belongings. “I was really lucky that a Berkeley rescue service picked up my chair,” she said.

While Sutter said in its release that the cessation of emergency services was “due to state seismic regulations,” panelists at the forum weren’t buying the explanation. Skinner couldn’t understand why Sutter couldn’t retrofit Alta Bates while Kaiser managed to retrofit its hospital in Richmond.

Pardue-Okimoto, also a nurse in the neonatal intensive care unit at Alta Bates, argued the not-for-profit corporation should be capable of affording the retrofit, citing Sutter’s $14 billion in assets. Arreguin pointed to $186 million in state bonds Sutter received to make capital repairs.

“An urgent care center is not a substitute for an emergency room,” Arreguin said.

He and other attendees at the forum made their position on the possibility of changes to Alta Bates’ services clear.

“Remember your hospital’s mission and do the right thing,” he said, “People’s lives depend on it.”