The Potential Volcanic Threat to San Francisco

Dormant California volcano Mount Konocti rises from the western shores of Clear Lake. By EggsyB.

In 1997, James Bond and Sarah Connor teamed up against the tallest and most powerful adversary of the nineties disaster-film revival: a volcano. The plot of Dante’s Peak is simple: a quiet town at the foot of a sleeping giant ignores its reawakening to attract more tourists and property investors. Pierce Brosnan, arguably the best 007, plays a volcanologist concerned that Dante’s Peak will erupt. Linda Hamilton of Terminator fame plays the town’s mayor, a mother of two, and eventually Brosnan’s love interest. Skeptics and politicians squander valuable time until the mountain explodes and all hell breaks loose, with our leads squarely in the middle of it.

The film draws from actual volcanic disasters, mainly the self-decapitating blast of Mount St. Helens in May of 1980. One real-life disaster was cited by name as the reason authorities hesitate to put the town on alert. A scare at California’s Mammoth Lakes in 1982 culminated in nothing but untold revenue losses for a town dependent on ski lodge and resort bookings. It took years for relationships between scientists and the region’s government officials to recover. Meanwhile, ground deformation and earthquake swarms continued at nearby Mammoth Mountain.

People seem to have forgotten the volcano. We know California for earthquakes and wildfires, not volcanoes. The 2022 eruption of Hunga Tonga–Hunga Ha’apai, loud enough to be heard in Fairbanks, Alaska, served as a public reminder. The eruption plume reached previously unseen heights, tinting the skies of the southern hemisphere. It also generated a tsunami that swept through the island nation of Tonga before fanning out across the Pacific, stirring up harbors in Peru and California. Then it was over, and the twenty-four-hour news cycle wiped the violent eruption from consumer thought.

Northern California’s volcanoes

Many believe the inland East Bay’s Mount Diablo is a volcano (it isn’t). Lava last flowed down a Bay Area hillside over nine million years ago. That rusty jagged mountainscape behind the Berkeley Hills is now the Robert Sibley Volcanic Regional Preserve. While that eruptive center is not this story’s focus, it is related. It represents a group of vents that form a chain of extinct volcanoes along the zipper track of the San Andreas Fault System. The most recent (and still active) of these centers is the Clear Lake Volcanic Field, home of the 4,305-foot Mount Konocti.

Mount Konocti gets its name from the Pomo people, whose land was first stolen from them in 1821. They very much still exist, having known the lake and Konocti, or Mountain Woman, for almost twelve thousand years. Their ancestors likely witnessed the last eruption, which geologists dated to around 11,000 years ago.

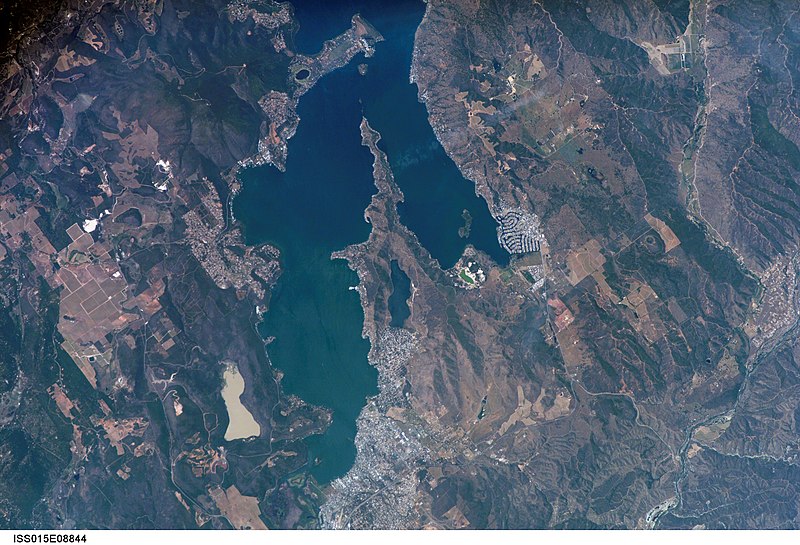

Activity isn’t limited to Mount Konocti herself. The entire lake has been subject to volcanism at some point in the complex’s lengthy history. The magma chamber, larger than that of Mammoth Mountain and its parent supervolcano, lies just four miles below the surface. Satellite cones have popped up where there used to be pine forest. Steam explosions carved out bays in the lake where now there are marinas. Their scalloped outlines are visible from satellite.

The most famous California volcano is probably Mount Shasta, the two-headed sentinel off Interstate 5 near the Oregon border. Ten thousand feet shorter than Shasta, Konocti has more in common with Lassen Peak, site of the state’s most recent eruption. Thick, syrupy magma at both centers built lava domes that plugged their vents until they exploded with force. Ash beds traceable to Lassen’s mineral profile have been found in drill cores across the Bay Area.

Satellite image of Clear Lake, California, showing a shoreline scalloped by explosions. NASA Public Domain.

What if an eruption happened tomorrow?

Remember when the sky caught fire? Expect anomalies like that as the weather cycles the volcanic ash out of its system. Stay indoors whenever possible once the ash begins to fall, and don’t even try to drive. “Ash” is actually pulverized igneous rock. A microscope reveals its menacing shape, spiky like a kidney stone or the asteroid from Armageddon. It clogs air filters, jet engines, and lungs. Cars cough and sputter to a stop not a mile from where they started. Ash melts in jet engines and spins into molten obsidian, grounding flights across Northern California. Too much ash in the lungs will mix with fluids naturally present to create a mucosal cement. Hold onto some of those N95s. Traditional masks like the ones we use for COVID won’t provide adequate protection.

Volcanic ash is surprisingly heavy, moreso than snow and ice. People who choose not to evacuate do so at their own risk. A roof cave-in caused the only death attributable to the 2021 Cumbre Vieja eruption on the Spanish island of La Palma.

Clear Lake is sacred to Native people and scientists alike, and is one of California’s lesser-known gems. Its scenic beauty was born from fire. Because of its lengthy record of destructive eruptions, the USGS designated the Clear Lake Volcanic Field a High Threat volcano. Our chances of seeing its inevitable return to activity are roughly one-in-ten thousand per year, slimmer odds than the Big One at about 1-in-200. That does not make it impossible. Mount St. Helens went from idyllic quiescence to catastrophic eruption in under two months. When it happens, dust off the old anthrax routine and seal off your doors and windows until the eruption ends. Drink only bottled water until city officials deem the supply safe. Remain indoors except to carefully clear your roof of ashfall.

And be sure to scoop some into a jar. Mount St. Helens’ ashes fetch up to sixty bucks on eBay.