The Other Unexpected Hazard on San Francisco’s Streets

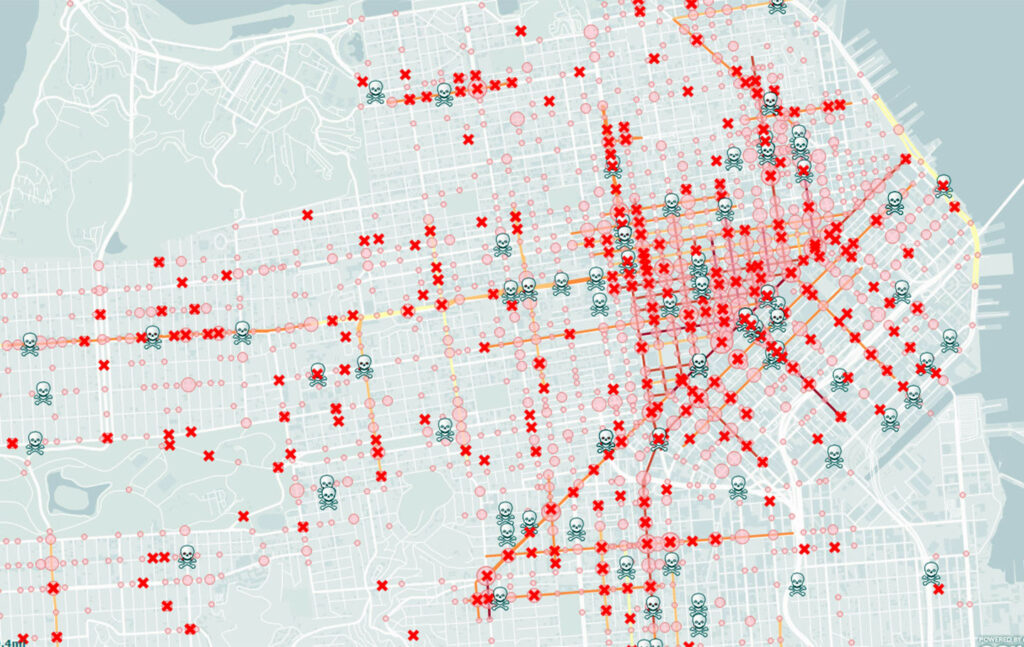

This map from 2015 accounts for 5,325 pedestrian and cyclist injuries as well as 127 deaths. Courtesy KQED.

San Francisco is not the Windy City, nor is it the state’s deadliest for pedestrians (that nefarious award goes to Concord, California). Nevertheless, the City by the Bay contains several spots where strange weather, extreme geography, and a rigid urban grid intersect. Two maps, one of our breeziest streets, the other our most accident-prone, reveal many in close proximity to each other. One block south of the notoriously windswept meeting of Geary and Masonic is Masonic and Anza, site of three recent head-on collisions. Six more occurred on Eddy Street a block north of allegedly brisk Polk and Turk. These vortices of blustery misfortune have seemingly produced some of the gustiest—and most dangerous—junctions in town.

Portola and Evelyn Way

Between Twin Peaks and Diamond Heights lies a mini-mountain pass that carries Portola Drive. It’s a natural notch in the landscape connecting Noe Valley and West Portal. Habitually onshore winds accelerate as they funnel through the gap, gusting at around twenty-five miles per hour. It’s more intense at the top of Twin Peaks, strong enough to steal one’s hat off their head.

Half a mile east of Evelyn and Portola, the wind pours into Noe Valley. There the street unbraids into three separate strands: Clipper Street, Diamond Heights Boulevard, and the continuation of Portola Drive. Heading west on Clipper towards Portola, the speed limit increases to 35 MPH. However, where Diamond Heights Blvd. begins, the limit decreases to 30. At Clipper and Portola, four head-on collisions have occurred since 2018.

Ocean Avenue and Mission Street

The wide-open valley between Glen Park and Excelsior offers an ideal setting for those onshore winds to fan out. It’s normal to go from cool, still air into a harsh headlong breeze just by rounding a corner. The neighborhood’s off-center street grid helps, with sharp corners of apartment buildings partially breaking it up. One exception is Ocean Avenue, which provides an east-west channel for the cold Pacific winds.

When SFGATE editor Dan Gentile set about mapping San Francisco’s windiest cross-streets, Ocean Avenue and Mission Street made the list. Six blocks south of the breezy intersection, a different phenomenon is also breaking records. Since 2018, eleven people have been struck by cars at Mission Street and Geneva Avenue.

Market Street—the whole thing.

A section of map featuring permitted vehicle crossings of the otherwise carless Market Street. The busy thoroughfare went “car-free” in January 2020. Courtesy MUNI.

Market Street might be the most well-known San Francisco thoroughfare. It is also perhaps the most dangerous. The hazards are many: armed robbery, open gunfire, racially-motivated stabbings. Market Street is involved in the city’s most notorious intersections, for wind and vehicular manslaughter.

It’s unclear why Market Street harbors such risks. The reason for the turbulence however is obvious. Air is not an aerosol. It behaves like a liquid, taking paths of least resistance around any obstacle. Skyscrapers line the artery from Van Ness to the waterfront, forming an urban canyon like those of New York City. The wind squeezes through the chasm and speeds up, wrapping around highrises and coming down hard on drivers and pedestrians.

From Van Ness to the Waterfront

An abrupt transition from mid- to highrise buildings at Van Ness Avenue dramatically alters the air’s fluid dynamics. In fact, that particular junction accrued the most suggestions when Gentile polled Twitter for his article.

“San Francisco Planning Department Chief of Staff Daniel Sider noted the Van Ness corridor from Civic Center to south of Mission Street as a prime candidate for windiest street. The blocks around Van Ness and Market were perhaps the most popular suspect from Twitter commenters, with several people pointing to Fox Plaza as a particularly windy spot. Architect David Baker agreed with Fox Plaza as a likely candidate. ‘Wind comes around that sucker and can knock you off your bike,’ he said.”

Van Ness and Market, suspected center of the vortex, is busy and intimidating whether you walk or drive. Regardless, worse crossroads exist in San Francisco. One block east at 10th and Mission has seen twenty-seven vehicle impacts throughout the last four years. The wind-tunnel effect is strong along Market between 5th and 8th Streets, where twenty pedestrians so far have been struck by cars.

From Van Ness to Castro

Advocates for freeway removal often cite the perilous meeting of Market and Octavia in their work. If you’re unfamiliar, it’s where the freeway portion of Route 101 touches down and Octavia Street begins. Thirty-seven of the seventy-three car crashes along this treacherous stretch of Market between 2018 and now happened here. One block up, Market and Guerrero saw eight head-on collisions.

The wind courses downhill at various speeds depending on the pressure system present. It’s sometimes fast enough to parachute your coat, tussle your scarf, knock over your toddler. Picture that happening at the bottom of a freeway off-ramp, where motorists driving at highway speeds bet against yellow lights. As seen in San Jose last week, kids are especially vulnerable.

Taylor and O’Farrell

Like the Market Street corridor, Taylor Street is buffeted by several prominent highrises, some of them among the city’s tallest. A strong sea breeze almost seems to prefer this touristy avenue stemming from Market and ending in North Beach. It is said to be strongest in the Tenderloin, at Taylor and O’Farrell Streets. I quickly learned when I lived on O’Farrell to always anticipate a powerful crosswind at Taylor.

Two blocks south of this windswept nexus is Taylor and Eddy, where drivers struck fifteen people over a four-year course. What makes this particular San Francisco street a hotspot for pedestrian casualties? Maybe the breeze ushers their cars through at these breakneck speeds. Maybe these unusual loci where air, people, and cars collide are evidence of something preternatural. Could they represent what eccentric Ivan T. Sanderson called “vile vortices,” of which the Bermuda Triangle is a famous example?

According to citizen advocate group Walk San Francisco, “around 30 people are killed and more than 500 severely injured each year citywide.” Whatever the cause, it can’t be irresponsible motorists protected by airbags and a steel cage. Drivers mean dollars coming into the city, and as for defenseless pedestrians, San Francisco couldn’t care less. So it has to be someone or something else’s fault: the wind, the fog, an ectoplasmic energy slick. Anyone but voters or the drivers themselves.

San Francisco is a city of perambulants, where tourists initiate themselves on our Thiebaudian streets. At least sixty percent of SF residents ride MUNI. Some like myself have been lucky enough to walk to work.

But it’s their fault for putting themselves out there, right? Whoever says otherwise must be spitting in the wind.

Jake Warren is a queer Indigenous nonfiction writer and San Francisco resident tired of nearly dying on their walk home from the store.