Inside San Francisco’s Tech Startups: An Outsider’s Report

Anna Wiener was a Silicon Valley insider with an outsider’s disposition.

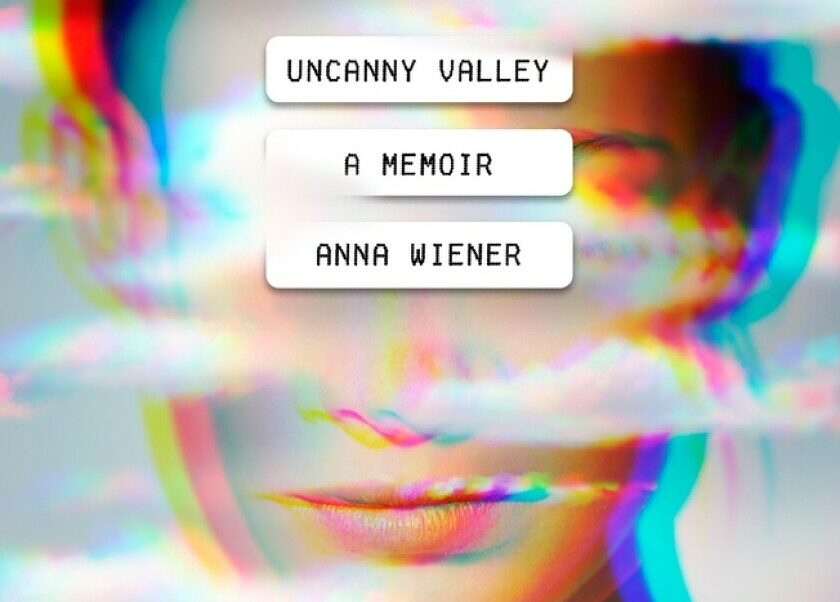

Her 2020 memoir, Uncanny Valley, documents her observations as an employee across three tech startups during the 2010’s, a pivotal decade for the tech industry and the world at large.

Unlike so many young college grads (and dropouts) eager to seize a title in San Francisco’s burgeoning startup scene, Wiener was not immediately enchanted by the prospect.

In her early twenties, she worked as an assistant at a small literary agency in Manhattan. She had a “fragile but agreeable life.”

Her plight in the book publishing world was familiar.

It was one of precarity. It was “privileged and downwardly mobile.” It was a modest life etched on a wavering limb of an increasingly anemic industry.

Beyond standard participation in the collective scroll, the products of Silicon Valley held little interest to Wiener. She was just like any other twentysomething in America with a smartphone—a little addicted, a little afflicted.

That is, until she discovered a startup that seemed to prize her interests.

Helmed by three perky male founders, the startup claimed the potential to revolutionize the book publishing industry. Their product was an e-reading app, boasting a vast library of titles accessible to those willing to pay a modest monthly fee.

“There was something unusual and attractive about people who had a vision for how the industry could evolve and a green light to get it done,” Wiener recalls. “I wanted in.”

And so, the literary romantic shook the cold claws of San Francisco’s technocracy.

What follows is a series of searing reports from the bloated bubble of Silicon Valley’s hive mind, as Wiener indulges both her ambition and her ambivalence within an industry marching relentlessly forward.

Below, I’ve rounded up the highlights for the pleasure of the precariat class.

On San Francisco

“San Francisco was an underdog city struggling to absorb an influx of aspiring alphas…The city, trapped in nostalgia for its own mythology, stuck in a hallucination of a halcyon past, had not quite caught up to the newfound momentum of tech’s dark triad: capital, power, and a bland, overcorrected, heterosexual masculinity.”

“People slept and shat and shot up in the train stations, lying beneath advertisements for fast fashion and productivity apps, as waves of commuters stepped delicately around them. I woke up one morning to the sound of someone howling for mercy on the corner of my block: a woman screaming bloody murder, dragging one leg, wearing nothing but a torn T-shirt emblazoned with the logo for a multinational consumer-electronics company…I had never seen such а shameful juxtaposition of blatant suffering and affluent idealism.”

“The neighborhood had incubated the sixties counterculture, and nearly fifty years later nobody seemed willing to give that identity up…It was possible that the tourists trawling the commercial strip mistook San Francisco’s homelessness epidemic for part of the hippie aesthetic. It was possible that the tourists didn’t think about the homelessness epidemic at all.”

On Silicon Valley culture

“The fetishized life without friction: What was it like? An unending shuttle between meetings and bodily needs? A continuous, productive loop? Charts and data sets. It wasn’t, to me, an aspiration. It wasn’t a prize.”

“It was reassuring to remember that the jobs we all had were fabrications of the twenty-first century. The functions might have been generic—client management, sales, programming—but the context was new. I sat across from engineers and product managers and CTOs, and thought: We’re all just reading from someone else’s script.”

“Efficiency, the central value of software, was the consumer innovation of a generation. Silicon Valley might have promoted a style of individualism, but scale bred homogeneity.”

On the plight of the millenial generation

“Those who understood our cultural moment saw that selling out–corporate positions, partnerships, sponsors–would become our generation’s premier aspiration, the best way to get paid.”

“My friends were hardworking and committed, but their vocations were poorly compensated, and against that rubric their life choices were wholly unimpressive. They were the sort of people some tech workers looked down on for not contributing meaningfully to the economy, though the derision cut both ways—if anyone our age had ever introduced himself as an entrepreneur, my friends would have laughed themselves into fits of smug superiority.”

“We were too old to use innocence as an excuse. Hubris, maybe. Indifference, preoccupation. Idealism. A certain complacency endemic to people for whom things had, in recent years, turned out okay. We had assumed it would all blow over. We had just been so busy with work lately.”

On the rise of technology

“I understood my blind faith in ambitious, aggressive, arrogant young men from America’s soft suburbs as a personal pathology, but it wasn’t personal at all. It had become a global affliction.”

“The platforms, designed to accommodate and harvest infinite data, inspired an infinite scroll. They encouraged a cultural impulse to fill all spare time with someone else’s thoughts. The internet was a collective howl, an outlet for everyone to prove that they mattered…People were saying nothing, and saying it all the time…People were giving themselves away at every opportunity.”

“The novelty was burning off; the industry’s pervasive idealism was increasingly dubious. Tech, for the most part, wasn’t progress. It was just business.”