Books from Banned Countries Part 4: Somalia

This is part of our Books from Banned Countries series. You can see them all here.

You may think you know nothing about Somali literature, but you’re mistaken. Okay, perhaps you’re right and you can’t name a single Somali author.

But unless you’ve been living under a rock somewhere way, way out, you’ve at least heard of one: Warsan Shire.

The Kenyan-born, London-raised and educated British Somali writer and poet became a bit of a pop sensation when Beyoncé used parts of her poems for Lemonade. (And you’ve heard of Lemonade, right?) Yes, the “you can’t make homes out of human beings, someone should have already told you that. And if he wants to leave then let him leave,” advice comes from the 28-year old creative writing graduate and London’s Young Poet Laureate.

You may be asking yourself; isn’t this series called “In Translation”? What translation is needed if the literature you’re presenting is originally written in English? Moreso, in this case, written by a poet who spent most of her life in London? Hey, we’ve never claimed it wasn’t messy. This is why we waded into the whole “what is national literature?” question when discussing Libya and came out with no answer because, really, there isn’t one. Not a good or easy one, anyways.

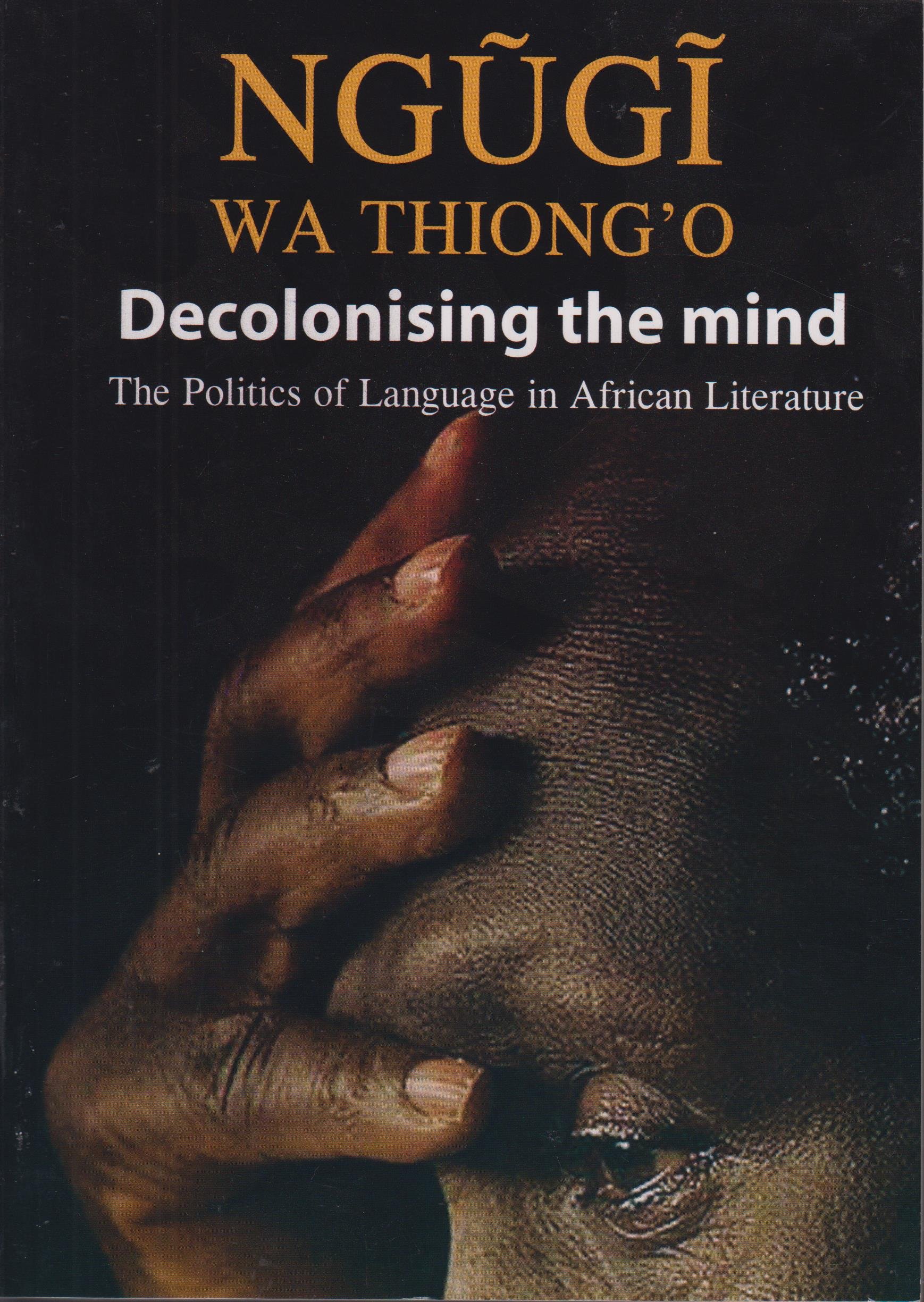

There are kinds of literature that go through entire periods of being written in languages that are not native to the culture or the land. And then there are literatures that coexist in several languages. If this is a topic that intrigues you, you may want to start your research with Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o‘s Decolonising the Mind.

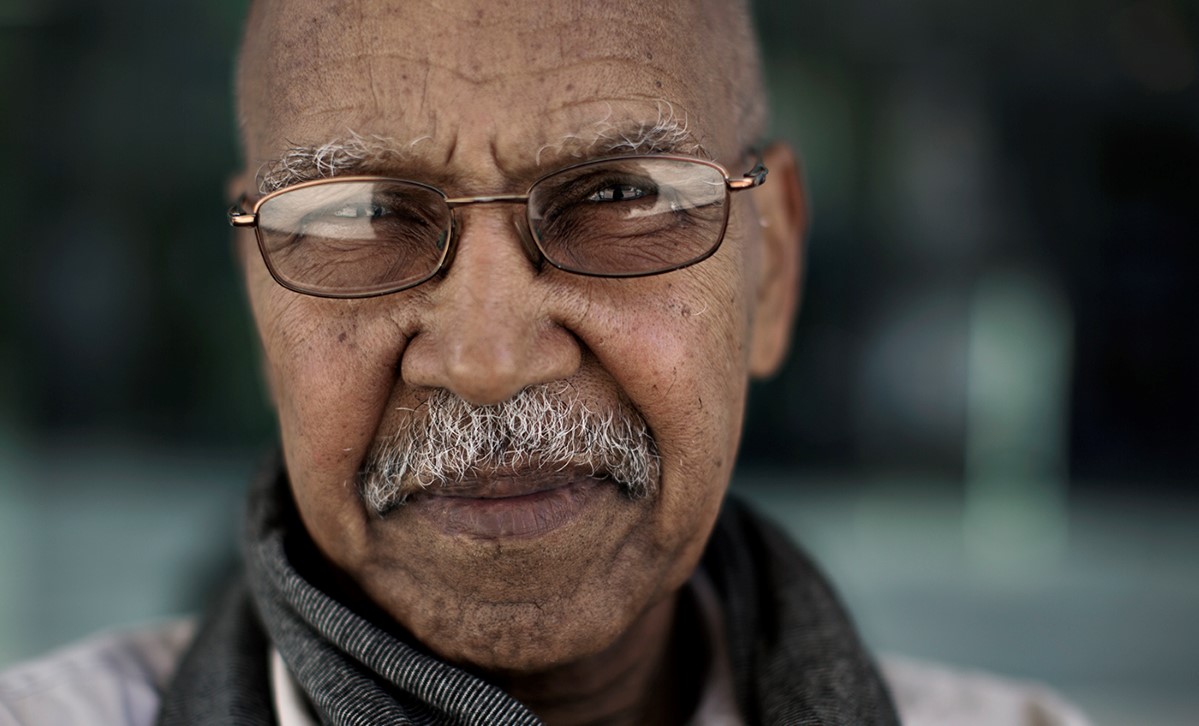

While the Kenyan Ngũgĩ began writing in English and then switched to Gyiuku, the most famous Somali author (and, like Ngũgĩ, a perennial Nobel favorite) Nuruddin Farah started off in Somali but wrote all of his novels in English. Which one to start with?

It really doesn’t matter, as long as you read something. The Blood in the Sun trilogy is probably the best known but read anything you can get your hands on. You owe it to yourself because the writer who has lived in exile since the mid-70s, when he received warnings that the government was planning to arrest him over the contents of his novel, and whose impetus to write has become “keep [his] country alive by writing about it” does it so beautifully.

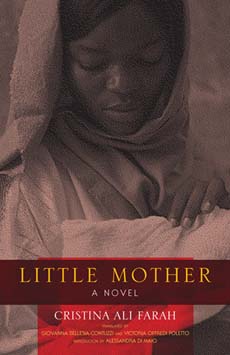

English is not the only “foreign” language that Somali literature is written in. Because of the colonial past, there is also the Italian-Somali part of it.

For the academically inclined (and Italian-speaking) among you, there’s a study by Laura Lori. Those only interested in fiction should dip into Little Mother by Italian-Somali author Cristina Ali Farah. One can only hope that the recent craze spurred by Elena Ferrante will result in more translations from Italian into English, and Cristina Ali Farah is definitely on at least one “must translate” list. For Somali writers writing in Arabic, consult the ever reliable Arabic Literature (in English).

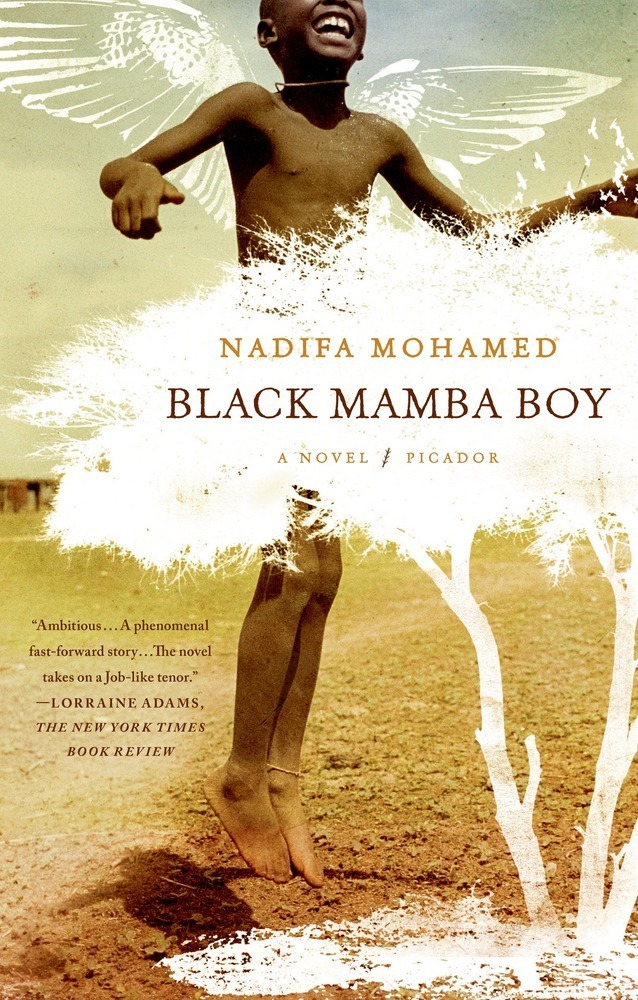

Back to authors writing in English: Black Mamba Boy by Nadifa Mohamed, shortlisted for the Orange Prize, received mixed reviews from some.

Personally, I found that its story of a street child captured the history, lives and migrations in the region known as the Horn of Africa really well. Another reason to include it here is the fact that it partly takes place in the port of Aden and Yemen will, hopefully, be the final installment of this series. (And let me just throw in here another book, by an Eritrean author, talking about refugees: Abu Bakr Hamid Kahal’s African Titanics.)

All the authors discussed in this segment have something in common: they live in diaspora. Because this entire series discusses literature from nations that have, in the last decade, produced the most refugees and because this fact has been used by populist politicians all over the western world for scare purposes without as much as an acknowledgement that it is partly western politics that caused the crisis; perhaps it’s appropriate to close with the same poet we opened with. In 2015, at the height of the refugee crisis in Europe, we were reminded that “better life” was a luxury that most refugees had no aspirations for.

For many, it was just the life they were searching for.

After all, “no one leaves home unless/home is the mouth of a shark”.