“I simply had a loopy plan that I executed with maniacal energy over 24 years, and I kind of pulled it off.”

So says prolific singer-songwriter and record producer John Vanderslice in the final chapter of TrueAnon Presents: “Keep the Dream Alive,” a five-episode podcast series on the history of his legendary analog recording studio Tiny Telephone San Francisco.

Of course, there’s no question whether or not Vanderslice pulled it off. He absolutely did.

Spurred by a feverish faith in the arts (and his own relentless demons), Vanderslice opened Tiny Telephone in 1997 in the “gutter of the Mission District” at 1458 San Bruno Ave. The studio offered little more than a modest assembly of gear in close quarters, but recording sessions were affordable and free from institutional overreach. Naturally, the artists followed.

By the time Tiny Telephone San Francisco closed in July of 2020, the studio had hosted the likes of Boz Scaggs, Deerhoof, Sleater-Kinney and Death Cab for Cutie. Meanwhile, Vanderslice’s maniacal energy sustained him, as he divided his time between producing, touring and recording music of his own.

Tiny Telephone SF was one of many casualties of rent leaps in the Bay Area, but its 2016 successor across the bay, Tiny Telephone Oakland, is still in operation today at 5765 Lowell St.

I spoke to Vanderslice about his outlook on the arts in the Bay Area, resisting nihilism, the utility of occasional drug use and his connection with TrueAnon producer Yung Chomsky.

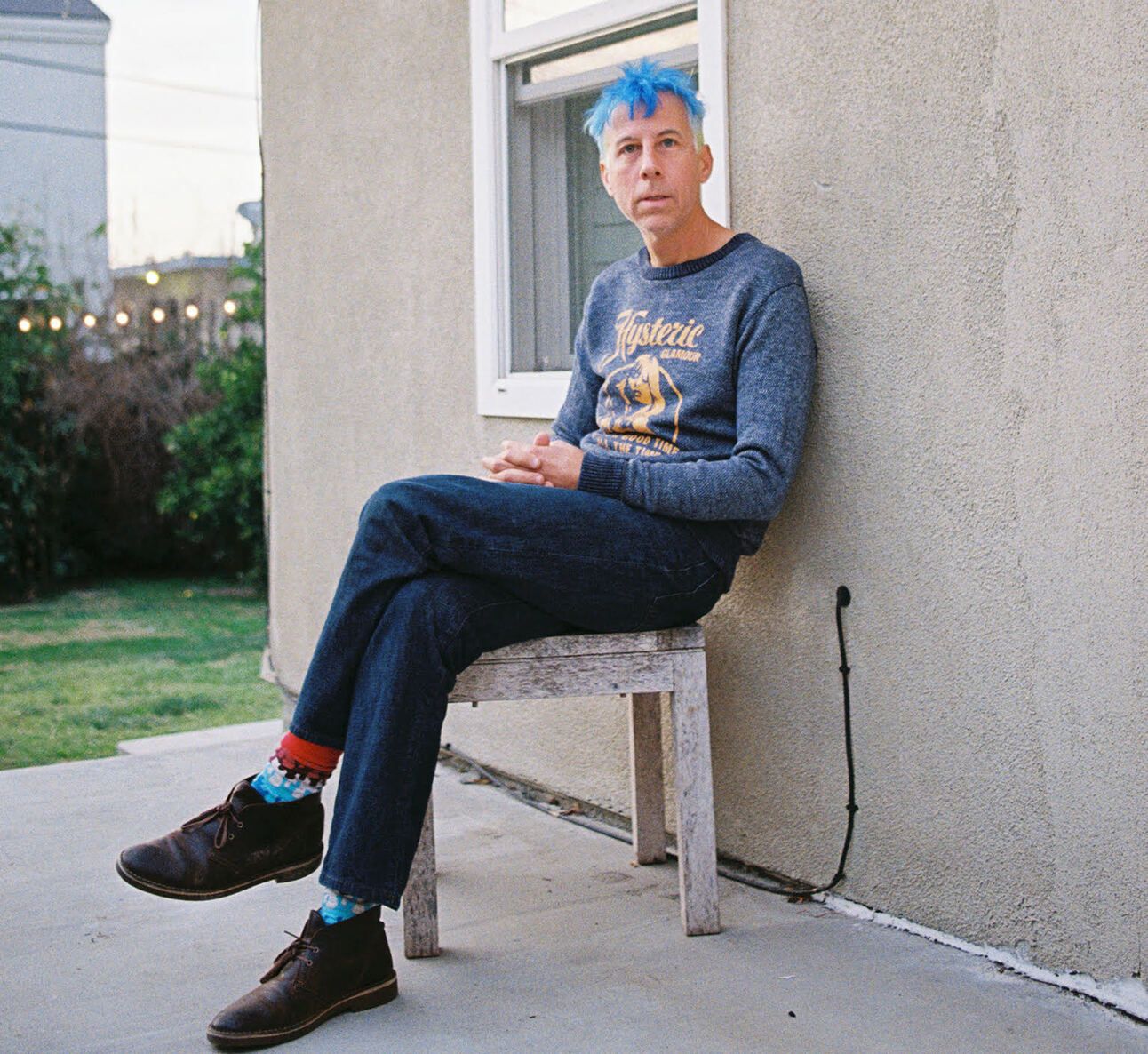

Singer-songwriter John Vanderslice, founder of Tiny Telephone recording studio in San Francisco and Oakland, is the subject of the recent TrueAnon podcast series, “Keep the Dream Alive.” (Photo courtesy Eleanor Petry)

Tell me about your connection with Yung Chomsky. Are you a TrueAnon listener?

JV: What’s wild is that I knew him way long ago. Way before TrueAnon.

[Chomsky] was very chill, and would often say “hi” at shows. I noticed that he was moving around a lot. I met him in London, and then I met him in New York, and then I met him in San Francisco. When I met him in SF, I was like, “Whoa, I’ve been seeing this guy for like 10 years, and he’s super chill, but he’s become more of a bubbling presence in my life.” At some point, he said that he’d started this podcast called TrueAnon. This was, like, three years ago. He wanted me to play some music on the Twitch stream for TrueAnon. That’s when I started listening to [the podcast] … I got obsessed with it.

He came up with this idea of a podcast [that would detail] the history of the studio. At first, I thought there was no way that that was interesting enough. My whole life is recording studios and all my friends own recording studios, so it doesn’t seem that unique or interesting. And then the more that I thought through his eyes, I was like, “Whoa, this is a really f—ed up story. This is very entertaining, honestly.”

Without [Chomsky] editing [the podcast], it wasn’t very good. He enforced this narrative on the pod, which is really smart. He knows how to get you invested in the story. The narrative is true, but you don’t necessarily feel it when you’re living it because life is chaotic. So he created a coherent narrative out of chaos. When I listen back, I’m amazed how good it is.

Music producer and singer-songwriter John Vanderslice fixes gear at his recording studio, Tiny Telephone San Francisco, which he ran from 1997-2020. (Photo courtesy John Vanderslice)

There’s a consistent element of subversiveness in both your art and your lifestyle. How has this wariness of corruption in high places evolved over time, and how has it informed your music?

JV: Once I was reading this essay about a post-punk rock critic. They were interviewing this critic, and they were asking him why he gravitated towards certain hardcore bands. He said, “I like when the ideas they express are antisocial and wrong.” He said it in a way that was very matter-of-fact, like, “I’m just drawn to these things.” Then I realized it clicked with me. I guess I have some of that, too, because I like either deeply political stuff or dirty, amoral, f—ed up music. It’s either rap or some grimy-ass punk or post-punk or some f—ed up electronic music. It was either Diamanda Galas or Arca. Or it’s the Geto Boys or JPEGMAFIA. It’s just gotta be ratty.

I always imagine that I’m better in theory than in practice. I’m better from a distance. I always notice that people love me right when they meet me, if they have a limited or superficial knowledge of me, but I think [the] day-to-day experience of me might be tiring.

I do think that I’m an edgelord, which is good and bad. It’s kind of entertaining, but if you’re dating me, then you have to endure me posting 50 memes a day of total garbage and mind pollution. So all these things have a double-edged sword. I can’t go to a Whole Foods without stealing from it. I need the serotonin.

I think it’s the same in music because sometimes I listen to my music and I wish there were a little less ideas in here. I wish there was a little less biography and a little less story and a little less didacticism. I like some of my early songs, and then some of my other early songs are so textbook, like, “This guy is so invested in having you know that he knows things.” Sometimes you want someone to be chill, and I feel like maybe sometimes I’m not chill. But the good part about me is that I’m very entertaining in small doses.

It’s all a joke to me. And I’m deeply serious about a lot of stuff, but there is a part of me that can’t believe the theater of what we have to endure. I just can’t believe that the veneer hasn’t been rubbed off by now.

A control room at Tiny Telephone San Francisco featured a Neve 5316 console. The studio recorded albums for numerous esteemed indie rock bands including Death Cab for Cutie, Sleater-Kinney, Okkervil River, Deerhoof, the Mountain Goats, the Magnetic Fields, Tune-Yards and Spoon. (Photo courtesy John Vanderslice)

On the podcast, you talk about resisting practical concerns in favor of the “maniacal dream.” Do you have any thoughts to share with young artists and entrepreneurs who are chasing maniacal dreams of their own?

JV: I feel lucky, for one thing, in that I was operating decades ago when there wasn’t climate doom certainty yet. I can’t imagine [opening a studio] right now because I’ve always been prone to depression, and I’ve always been prone towards inaction, in a way. I do think that you internalize the profound knowledge of our own doom, so I’m not sure that right now I would believe that building some scrappy-ass recording studio matters anymore. I’ve gotten more nihilistic. … Deep down, we know that nothing is important. If you’re a sensitive artist, you have this existential problem with every decision you make. It’s a demonic outrunning.

When you’re a delusional art person, you’re like, “I’m just gonna record, and then someone’s gonna figure out that I’m really good, and I’ll get out of this mess.” But after 15 years of that, you get so beaten down that you’re trying to outrun this version of you that’s a loser. … So I started the studio because it felt like a way out of being a loser. It wasn’t that I believed in the future, and it wasn’t that I thought it would get me anywhere. I just didn’t want to be ashamed.

It wasn’t until much later when I started coming to peace with all that stuff. From the advice side: Embrace that you’re being hunted down by demons. Maybe the beginning of your healing is to just run as fast as you can from those demons, and try to do what they’re telling you to do. Because whenever you see anyone do anything, you’re like, “Nah, it’s not that they want something. It’s that they’re being hunted down by demons.” Every f—in’ time. Yeah, Kanye wanted to be big, and he wanted to win a Grammy, but he also had demons beyond belief.

John Vanderslice performs in the middle of a crowd in Columbus, Ohio. (Photo courtesy John Vanderslice)

Friends of yours jokingly refer to you as a “cult leader” and a “carnival barker.” You’re clearly a charismatic presence. More recently, however, you’ve expressed interest in becoming a “receding narrator,” at least in your music. Can you tell me about that transition?

JV: You can only go so far with this narcissistic position in making art. I think that the more electronic music I listen to, the more I fall under the spell of these communities where they devalue the public face of the artist. We know Aphex Twin. He’s an outlier. There are a few outliers, but Autechre? What do I know about them? Literally nothing. They prize this faceless presentation. Part of it is that you don’t have this singing narrator that is assumed to be giving this confessional story.

I like receding as a personality in music because I think that if you’re gonna have a long career, then you have to have different stages of that career. You should be confounding at times, or irritating at times, or predictable at times. Where I’m at now, I wanna shift into as much of an opposition to where I was 10 years ago, where I wanted to write about what was happening in my life and I wanted to be as honest and direct as possible. Now I’ve written hundreds of songs like that. I’m good. I wanna make more abstract and unique and potentially alienating music.

I’m putting out a record in September called “Crystals 3.0.” It’s 25 single-minute songs, and there’s simply no way that a high percentage of people who like my music are gonna like it. It’s not gonna happen. I’m not doing it so they don’t like it, and I’m not doing it so they do like it. I literally don’t care. I’m doing it because it’s fun. I’m doing it because that’s what I make when I go into a studio and that’s what I want to hear come out of the studio. … I burned out on the system of writing a song with a chorus, a bridge and an outro. I try not to think in those terms anymore. Of course it’s impossible, but I try not to adhere to any systems that I used to have in place.

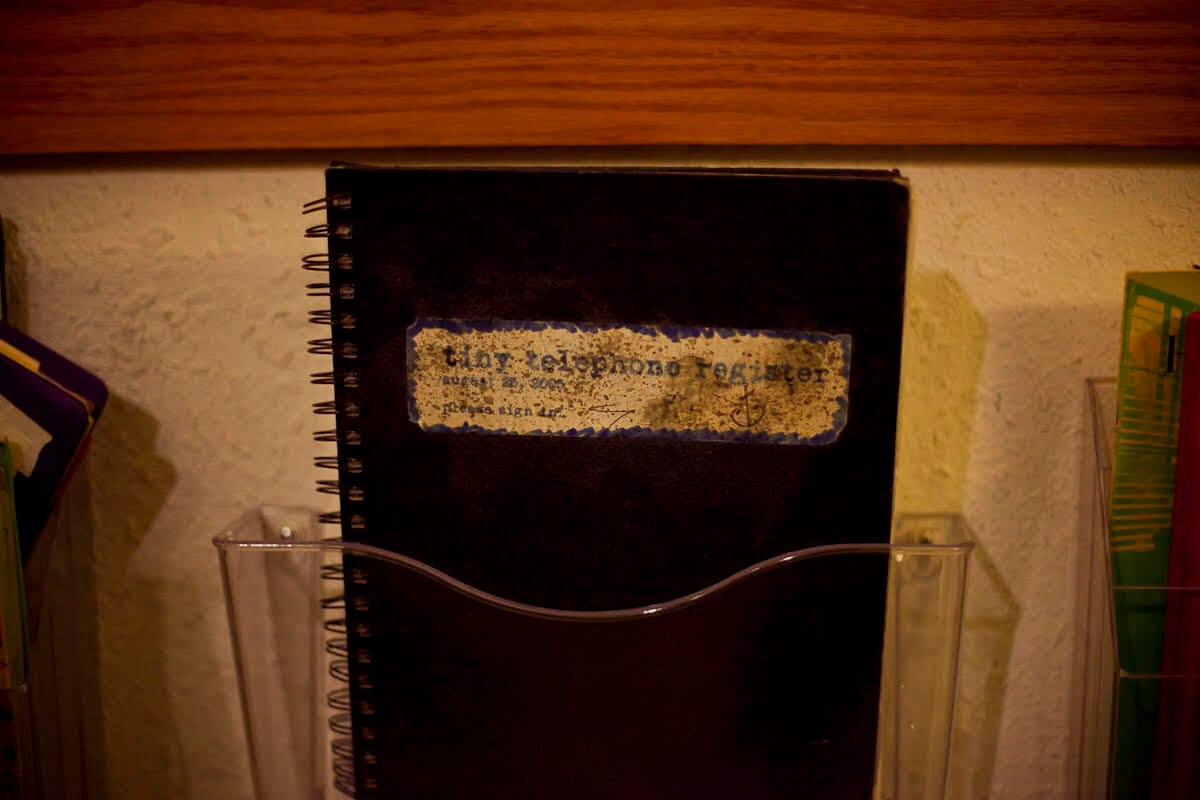

Tiny Telephone’s guest sign-in books, like this one at the studio in San Francisco, contain a rich musical history. (Photo courtesy John Vanderslice)

What are your favorite memories at the original Tiny Telephone studio?

JV: There were tons of amazing, creative connective moments. You’d be producing a record in one room, and then you’d check in on the other room, and sometimes it would be way better than what you were doing. It was always really exciting. Like maybe [a band next door] has a pedal steel player, and we need to have this goopy melodic overlay that isn’t doing anything too definite, and then you’d think, “Why don’t I just try to borrow the pedal steel player and see if they’d play on this record?” Then you’d try to talk them into it. That back and forth [between recording rooms] was really important because people in different bands would get to be friends. … It’s so much better to have a competitive, creative spirit with art.

We were just little rats renting a small piece of [our landlord’s] empire. They could’ve exterminated us, and they let rats live in their place. They’re heroes.

Tiny Telephone San Francisco closed in 2020, and you’ve since moved to LA. Do you have hope for the arts in San Francisco?

JV: The entry point to LA is still way cheaper than the Bay Area. In LA, rents are going up, but housing is going up constantly. Not so in San Francisco.

I think you should move to a city that is allowing and encouraging people to move there. The Bay Area is completely resistant to that. So you get old money and tech powerhouses, and the odd artist strolling in that gets invested and then suffocated. Whether you know it or not, the clock is ticking for when you leave. Every single person I know in LA is in the arts. It’s just a company town in the coolest way.

John Vanderslice sits outside his small backyard recording studio in Los Angeles. (Photo courtesy Eleanor Petry)

You opened Tiny Telephone Oakland in 2016. Do you feel that Oakland is a safer haven for artists and musicians?

JV: I rented that space in Oakland in 2010. We made the decision early on to move to Oakland because everyone was getting pushed out of San Francisco at some point. I thought Oakland was going to be the great hope for the Bay Area. I don’t actually believe that anymore. I think that Oakland is just another tech town. Oakland’s another deeply unfair, highly segregated, f—ed up, corrupt American city with a bunch of tech money. It’s kind of a bummer to me.

If I could pull up Tiny Telephone Oakland and move it to LA I would. LA doesn’t believe it’s a good place. LA doesn’t believe it’s this special left-wing progressive [city]. It’s just a piece of s—. And you like it more for that. The disparity in wealth in the Bay Area is f—ing insane.

I have a backyard studio [in LA]. I’ve had people record there, but it’s mostly just a private studio. It’s really an electronics studio. It’s really made for drug music, honestly.

You’re very open about your drug use. Has it influenced your music in any way?

JV: Whenever the first Silk Road [darknet market] popped up, I started dabbling in stuff. The stuff that I really enjoyed at the time was opium and pure pharmaceutical grade cocaine, which is very underrated. … I would say that cocaine affected my music zero percent. It’s just a very pleasant thing to do with your friends.

I noticed that there was a lot of crystal MDMA on the dark web, and I began to research it. … You know when you’re a kid, and you don’t know what drugs are, and you think [doing drugs] is like this crazy, all-enveloping physical-slash-spiritual experience? Then you do drugs, and you realize that they’re actually really complicated. MDMA reads the closest to your childhood vision of a drug experience.

I think I bought 20 grams of MDMA, and [my friends and I] came up with this pact that we’d take it every three months. You don’t wanna push it more than that. So we started taking it, and [a] friend [who] was obsessed with electronic music … would DJ these nights. These nights really started changing what I wanted to hear musically. I wanted to start hearing glitchy, distorted, repetitive and unsteady musical information. [He] started developing his own narrower tastes in electronic music as we kept doing it. So we all got an education while on a very convincing, immersive drug. It completely changed the music I was making.

John Vanderslice’s current shows feature him playing guitar and talking about his life, but he plans to change that up for the next album. (Photo courtesy John Vanderslice)

What are you excited about right now? What’s next?

JV: In May [and June], I have a monthlong tour in Europe. The setup I’m doing now is I play electric guitar with an old ’80s roll-in drum machine, and I have some guitar effects and vocal effects, and it’s in some ways a very literal reading of my catalog. A lot of the show is that I take questions and I speak very directly about my own life. It’s probably half dialogue. My friends pushed me to not do that anymore. They told me, “You need to actually integrate electronic music into what you’re doing now.” My live show can’t be a live show from 15 years ago. It has to be totally different.

When I get back, I’ll finish up “Crystals 3.0.” That means that from that point on, my entire slate is clean. In two years, I will have put out two records and two EPs, which feels really good for me. And it’s been a real reset in the kind of music that I’m making. The next step is getting a completely different set that is radically different from anything I’ve ever done, and then figuring out the next record I want to make.

The post John Vanderslice on Drugs, Dreams, & Legendary Analog Recording Studio appeared first on Broke-Ass Stuart's Website.